Idi Amin feeding his opponents to crocodiles, Jean-Bedel Bokassa crowning himself emperor, Mobutu Sese Seko building a replica of Versailles in the Zaïrian jungle – Africa’s most vicious and predatory dictators have cast a long shadow over contemporary representations of the continent. The arbitrary and often brutal rule of these leaders played into existing colonial era stereotypes of African politics as being dominated by merciless tyrants and “senseless” political violence, which are often resurrected by the international media to explain a particular conflict or bout of political instability.

In reality, of course, managing an authoritarian state is a difficult job. You can’t keep a large country stable for a long time just by telling everyone that you are really powerful.

Instead, you need to manage competing factions, find ways of demobilizing protests, and make sure that the security forces are paid. In our new book, Authoritarian Africa: Repression, Resistance, and the Power of Ideas, we show that the authoritarian leaders who managed to maintain stable one-party states in the 1970s and 1980s, and their contemporary counterparts who govern repressive states today, need to be smart and adaptable in order to survive.

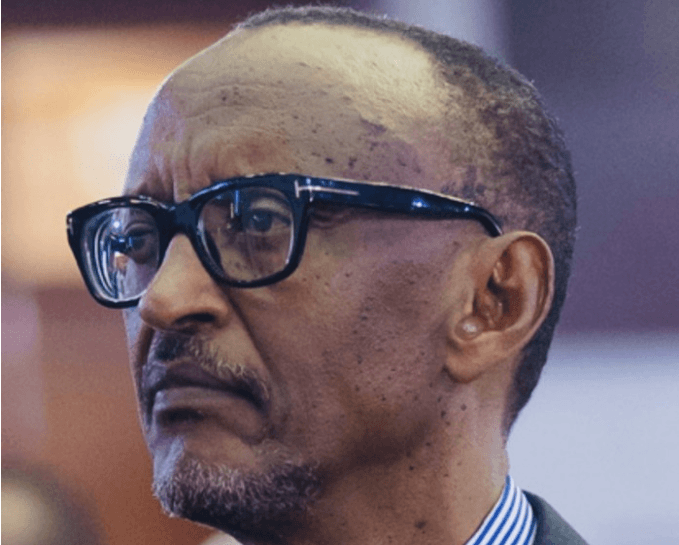

There are a great deal of different kinds of authoritarian system in Africa, from military rule to Apartheid, and from colonial exploitation to Paul Kagame’s Rwanda. As protesters and activists in Sudan stressed earlier this year after the fall of dictator Omar al-Bashir, authoritarianism is not just a person, it is a system. But successful authoritarian leaders often have one thing in common: they don’t only rely on repression. Instead, they co-opt some groups to secure their support and use popular ideas to try and legitimate their rule.

It is only by understanding how these different strategies reinforce each other that we can explain the durability of some of the continent’s authoritarian regimes.

Authoritarianism 2.0

It is easy to think of authoritarianism as a thing of the past, given the reintroduction of elections in the early 1990s. But in reality, many — some would say most — African people still live under authoritarian political systems in which elections are held but political rights and civil liberties are not respected. In this new kind of authoritarianism, opposition parties campaign with one hand behind their back and power never changes hands.

The key defining feature of an authoritarian government is therefore not whether or not it holds elections, or has a parliament, but whether power ultimately rests on the use of force. Ultimately, all authoritarian regimes are founded upon violence – sometimes embedded within a militarized state and society itself, sometimes visited upon citizens only occasionally, and otherwise held back as a looming threat.

While some dictators have tried to keep power solely by terrorizing their citizens, few political systems can survive through repression alone. This is particularly so in many African countries, where the formal — and physical — reach of the state increasingly tapers off outside of major cities and towns. This renders it virtually impossible to establish totalitarian surveillance states where citizens’ every conversation could, potentially, be being monitored.

More successful authoritarian regimes therefore combine coercive tactics with those of persuasion — giving key groups and constituencies reasons to accept the system, rather than just forcing their acquiescence through oppression and cruelty.

How to make friends and influence citizens

The more resilient of Africa’s authoritarian regimes, for example, have bought support from powerful local elites, soldiers, particular ethnic groups or political influencers through building them into extensive patronage structures where state resources are cascaded down chains of patron-client links. In so doing, they may assemble a large, and often diverse, group of communities who rely on the regime’s survival for their prosperity.

Many authoritarian African leaders have also successfully leveraged lasting support from the international system by persuading certain major powers of their value as allies. Despite clear authoritarian abuses, both Yoweri Museveni’s government in Uganda and Paul Kagame’s in Rwanda have enjoyed spells of being “donor darlings”, receiving large amounts of foreign aid.

The more that support can be co-opted both domestically and internationally, the less it has to be coerced.

The power of ideas

It is important, however, not to view consent within all authoritarian regimes as simply a transactional affair. Just as in more democratic states, the legitimacy of authoritarian systems derives from a complex range of inter-connected forces. In some cases, successful authoritarian leaders harness the power of ideas to support their rule. To do this, they often tap into existing narratives that resonate with at least some of their people.

In states with a history of internal conflict or civil war, for example, an authoritarian political structure that guarantees peace, stability and national unity may be seen as a necessary evil. Authoritarian governments like that of Uganda’s National Resistance Movement (NRM) have successfully played on this theme over many decades. In the country’s 1996 general election — the first held for a decade — the NRM’s campaign materials displayed the skulls of victims of Uganda’s recent civil war, ended by the NRM, under the tagline “Don’t Forget the Past —YOUR VOTE COULD BRING IT BACK!”. The ruling party repeated the tactic twenty years later, in 2016.

Many other post-independence authoritarian leaders have sought to legitimise their rule through appeals to traditional authority and a romanticised version of African history. Malawian president Hastings Banda, for example, styled himself Ngwazi (“chief of chiefs”) while Zaïrian dictator Mobutu Sese Seko renamed cities, towns, and the country itself according to “authentic” pre-colonial names. Harnessing the popularity of traditional leadership — surveys find that the majority of citizens would like to expand the power of chiefs in most African countries — can be a powerful force of legitimization.

Similarly, successive African authoritarian regimes have also advanced the argument that democracy — or, at least, “Western-style” democracy — is either “unAfrican” or unsuited to the continent’s cultures and needs. This has often been premised on the need to return to pre-colonial forms of rule. Former Tanzanian president Julius Nyerere, for example, banned all political parties except for his own, arguing that multi-party democracy was simply “football politics” and that authentic African governance should take its inspiration from the past, when “elders sit under the big tree and talk until they agree”.

More recently, Paul Kagame has become the most famous advocate of the argument that “western” democracy is unsuited to African conditions. The effectiveness of this claim, of course, depends on whether governments can actually deliver stability and development. In the 1980s it became clear that many one-party states had failed on this, which contributed to their collapse. By contrast, Kagame’s arguments have so far been supported by the fact that Rwanda’s GDP has grown by more than 120% in 15 years, though the country remains below Syria and Zimbabwe in the Human Development Index.

When leaders do a good job of tapping into popular concerns and delivering services, the task of sustaining authoritarian rule becomes much easier.

Resistance

The importance of co-optation and the power of ideas to the success of authoritarian leaders does not mean that citizens become happy to live under authoritarian rule. None of the political systems we have described would have survived without repression, and surveys consistently find that strong majorities favor democratic government in almost every country. Moreover, recent political transformations in authoritarian countries from Sudan to Ethiopia and from Burkina Faso to Gambia have demonstrated that African citizens are quick to topple authoritarian leaders when they see an opportunity to do so.

It is still important, however, to understand that the amount of repression a leader requires will be lower if they can co-opt support while managing public sentiment. Governing through force is much easier if you can get your networks and optics right.

How colonial rule predisposed Africa to fragile authoritarianism