By Mehul Srivastava in Tel Aviv and Tom Wilson in Nairobi

Inside the WhatsApp hack: how an Israeli technology was used to spy. Earlier this year, Faustin Rukundo’s phone started to ring at odd times. The calls were always on WhatsApp — sometimes from a Scandinavian number, sometimes a video call — but the caller would hang-up before he could answer. When he rang back no one would pick up.

Mr Rukundo, a British citizen who lives in Leeds, had reason to be suspicious. As a member of a Rwandan opposition group in exile, he has lived for several years in fear of the security services of the central African nation where he was born.

In 2017, his wife, also a British national, was arrested and held for two months in Rwanda when she returned for her father’s funeral. Unidentified men in black suits have previously queried her co-workers about her route to the childcare centre where she works, he says. His own name has shown up in a widely circulated list of enemies of the government of Rwanda titled “Those who must be killed immediately”.

In the two decades since Paul Kagame became president of Rwanda, dozens of dissidents have disappeared or died in unexplained circumstances around the world. In response, those willing to criticise the regime or organise against it, such as Mr Rukundo, say they have learnt to be cautious, masking their presence on the internet and using encrypted messaging services such as WhatsApp.

Faustin Rukundo at his home in the UK © Asadour Guzelian

But the missed WhatsApp calls were more ominous. Powered by a technology built not in Rwanda but in Israel, the calls were a harbinger of Pegasus, an all-seeing spyware so powerful that the Israeli government classifies it as a weapon. Developed and sold by the Herzlia-based NSO Group, which is part-owned by a UK-based private equity group called Novalpina Capital, Pegasus was designed to worm its way into phones such as Mr Rukundo’s and start transmitting the owner’s location, their encrypted chats, travel plans — and even the voices of people the owners met — to servers around the world.

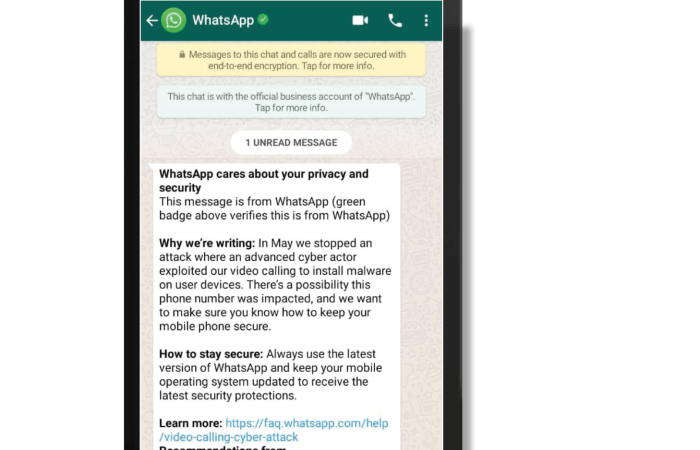

Since 2012, NSO has devised various ways to deliver Pegasus to targeted phones — sometimes as a malicious link in a text message, or a redirected website that infected the device. But by May this year, the FT reported, NSO had developed a new method by weaponising a vulnerability in WhatsApp, used by 1.5bn people globally, to deliver Pegasus completely surreptitiously. The user did not even have to answer the phone but once delivered, the software instantly used flaws in the device’s operating system to turn it into a secret eavesdropping tool.

WhatsApp quickly closed the vulnerability and launched a six-month investigation into the abuse of its platforms. The probe, carried out in secrecy, makes apparent for the first time the extent — and nature — of the surveillance operations that NSO has enabled.

In recent days, the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab, which studies digital surveillance around the world and is working in partnership with WhatsApp, started to notify journalists, human rights activists and other members of civil society — like Mr Rukundo — whose phones had been targeted using the spyware. It also provided help to defend themselves in the future.

Targeted: Frank Ntwali SENIOR OFFICIAL, THE RWANDA NATIONAL CONGRESS

An opposition activist, based in South Africa, Mr Ntwali’s travels and meetings are often described in detail in Rwandan pro-government media, and he receives regular death threats. Several of his colleagues in Uganda, Mozambique and other countries have either been killed or vanished in unexplained circumstances, or imprisoned in Rwanda. “We have been suspicious,” he says of how the information was leaking out. “Now at least we know.”

NSO — which was valued at $1bn in a leveraged buyout backed by Novalpina in February — says its technology is sold only to carefully vetted customers and used to prevent terrorism and crime. NSO has said it respects human rights unequivocally, and it conducts a thorough evaluation of the potential for misuse of its products by clients, which includes a review of a country’s past human rights record and governance standards. The company believes the allegations of misuse of its products are based on “erroneous information”.

The NSO Group said in a statement: “In the strongest possible terms, we dispute today’s allegations and will vigorously fight them. Our technology is not designed or licensed for use against human rights activists and journalists.”

But WhatsApp’s internal investigation undercuts the efficacy of such vetting. In the roughly two weeks before WhatsApp closed the vulnerability, at least 1,400 people around the world were targeted through missed calls on the platform, including 100 members of “civil society”, the company said in a statement on Tuesday.

This is “an unmistakable pattern of abuse”, the Facebook-owned business said. “There must be strong legal oversight of cyber weapons like the one used in this attack to ensure they are not used to violate individual rights and freedoms people deserve wherever they live. Human rights groups have documented a disturbing trend that such tools have been used to attack journalists and human rights defenders.”

The NSO headquarters in Herzliya near Tel Aviv, Israel

The two-week snapshot provides a rare glimpse of how some of NSO’s clients use its spyware — with greater frequency than previously known, and often to monitor people unrelated to terrorism or criminal activity.

Those targeted include people from at least 20 countries, across four continents, with many showing clear evidence that the attempted intrusions had nothing to do with preventing terrorism, says John Scott-Railton, a senior researcher at Citizen Lab. The targets include several prominent women who have had intimate material released; opposition politicians; prominent religious figures of multiple faiths; journalists, lawyers and officials at humanitarian organisations fighting corruption and human rights abuses. Some have previously been the subject of assassination attempts and face continuous threats of violence. It appears that the surveillance originates from multiple customers of NSO’s technology, he adds.

“This is in stark contrast to NSO’s claim that there is not a systematic pattern of abuse — rather, it indicates that there is a global pattern of abuse,” says Mr Scott-Railton. “The window that this represents shows us that anyone looking systematically at how this technology is used will find a similar pattern.”

Earlier research by Citizen Lab had already traced Pegasus to the phones of human rights activists, journalists and dissidents from at least 45 countries including Bahrain, Kazakhstan, Mexico, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. After years of criticism, NSO had claimed to have found only a handful of cases of abuse.

The victims of the attacks which placed spyware on their smartphones were contacted by WhatsApp on Tuesday

On the list of targeted individuals identified by WhatsApp, a considerable number were from Rwanda. The FT interviewed six with ties to Rwanda who have recently been informed of the attacks. The Rwandan government declined to comment.

In addition to Mr Rukundo, the Rwandan targets included: a journalist living in exile in Uganda, who had petitioned the government in Kampala to help protect Rwandans in the country from assassination; a senior member of the Rwanda National Congress, an opposition group in exile; and an army officer who fled the country in 2008 and testified against members of the Rwandan government in a French court in 2017.

“It’s a grave violation,” says Placide Kayumba, a Belgium-based member of Rwanda’s FDU-Inkingi opposition party, who was informed by Citizen Lab that his phone was targeted.

“It’s scary, not only due to the information I have exchanged as a human-rights activist and politician, but especially due to my private activities, my conversations with my family, with my friends, the private details that I have shared on the telephone.”

Targeted: Placide Kayumba OPPOSITION PARTY MEMBER

A member of the FDU-Inkingi opposition party, Mr Kayumba left Rwanda in 1994, aged 13, and now lives in Belgium. The leader of the FDU, Victoire Ingabire, was imprisoned for six years after she returned to Rwanda from exile in 2010. Mr Kayumba started to receive suspicious missed WhatsApp calls earlier this year. “All of my colleagues at the centre of the party are monitored and threatened on a daily basis with assassination, disappearance, imprisonment,” he says.

WhatsApp’s investigation could not determine which countries were operating NSO’s technology, only the telephone numbers of those who had been targeted. Rwandan dissidents caught up in the spying say they have no doubt who is responsible: their government. “We are always under watch,” says Frank Ntwali, a senior RNC official based in South Africa, who was advised by Citizen Lab that his phone was targeted. “This criminal regime is trying to silence its critics.”

Earlier this year, he says, parts of private conversations he had while in South Africa began to appear in pro-government Rwandan newspapers, suggesting someone or something had been listening. “We would read them, and we would wonder — how do they know? At least now we know.”

Mr Kagame, Rwanda’s president for the past 19 years, is a leader revered and feared in equal measure. He led the rebel army that seized power in 1994 bringing an end to a genocide that had killed 800,000 people in a matter of weeks. He returned stability to Rwanda and now claims to run a thriving economy, with annual growth at more than 7 per cent.

At the same time, his critics say, Mr Kagame — who was elected for a third term in 2017 with 99 per cent of the vote — has sought to silence opposition to his Rwandan Patriotic Front, both inside and outside the country. Starting in 1996, when Théoneste Lizinde, an RPF colonel, was shot dead in Nairobi, at least seven Rwandans — most of them former members of the regime — have been killed or seriously wounded in planned attacks outside Rwanda, according to Human Rights Watch.

Even before the WhatsApp hack, British police in London had warned at least one Rwandan activist who is now a UK citizen of a plot to kill him, according to documents seen by the FT. “Reliable intelligence states that the Rwandan government poses an imminent threat to your life,” read the police warning notice given to Rene Mugenzi. “You should be aware of other high-profile cases where action such as this has been conducted in the past. Conventional and unconventional means have been used.”

Other Rwandan nationals told the FT that they had been informed of threats to their life in France, Belgium and Canada. Those targeted by NSO’s Pegasus say the spyware was just the government’s latest tool to monitor them.

Targeted: Sulah Nuwamanya AID WORKER WHO FLED TO UGANDA IN 2014 A

Ugandan of Rwandan descent, Mr Nuwamanya left Rwanda after being warned by a school friend that his name had been mentioned in a meeting of security officials discussing threats to the state. In Uganda, he teamed up with a group of Rwandan women whose husbands had been critical of the Kagame regime and vanished under suspicious circumstances. Together they called on the government in Kampala to provide more protection to Rwandan dissidents in the country after colleagues were attacked.

In November 2017, one of his colleagues was shot at during an attempted kidnapping. Four months later, a friend was murdered after speaking to Mr Nuwamanya by telephone. After that he was taken into safe custody by the Ugandan police. “What we are saying is very simple: stop killing people, stop kidnapping us, stop illegal repatriation to Rwanda,” says Mr Nuwamanya. “They see me as a threat because I could push the Ugandan government to arrest some of their collaborators and spies.”

Mr Rukundo, the Leeds-based dissident, says his life has been “close to the edge” for a while. He works for a diplomatic team in the RNC and spent much of the last year trying to get other Commonwealth nations to recognise the deaths, disappearances and arrests that he says have marked Mr Kagame’s reign. Rwanda is due to host the Commonwealth summit next year.

“Mostly, I am meeting other African government ministers to warn them that in Rwanda, democracy is nowhere to be found. Human rights are nowhere to be found,” he says. “[So] they think I have a lot of information. They think that if they get what I have, they will have everything from the RNC.”

On a recent trip to Mozambique, he changed his travel plans at the last minute and says that he still found six men watching him at Maputo airport.

In spring 2019, another Rwandan, David Batenga, started noticing missed WhatsApp calls. Mr Batenga is well known to the Rwandan government. He discovered the body of his uncle Patrick Karegeya — the former Rwandan intelligence chief and founder of the RNC — in a South African hotel room in January 2014. Karegeya had been strangled. In August, a South African judge issued arrest warrants for two of the four Rwandans suspected of the murder, after the testimony of a police officer at the inquest linked the killing to Mr Kagame’s government.

Mr Batenga says he is worried about how the information stolen from his phone via Pegasus could have been used. He helped arrange a trip for a Belgium-based compatriot in August, who then vanished a few days after landing in Kampala, the Ugandan capital, despite taking precautions that included changing safe houses.

In other cases, those targeted by the NSO software are worried that knowledge of their conversations may have been used to target people in Rwanda with whom they have communicated.

This year, two members of the FDU-Inkingi party whose leadership returned from exile in 2010, have been killed in Rwanda and a third is missing. One was found dead on the edge of a forest, the other stabbed in the canteen at the health centre where he worked.

David Batenga, who believes his phone was infiltrated thanks to Pegasus

“I can’t say whether or not those killings are linked to the hacking of my phone,” says Mr Kayumba, who serves as the party’s third vice-president. “But it is clear that the discussions that we have with members of the party, notably those in Rwanda, are certainly monitored in one way or another, because we see the reaction of the state.”

Lewis Mudge, the Central Africa director of Human Rights Watch who was barred from entering Rwanda last year, says the digital surveillance continues an established pattern of international intimidation.

“When Patrick Karegeya was murdered, Kagame and those in his government revelled in his killing. It reinforced that they will silence those who they deem enemies without pity,” he says. “The message is clear: you can run, but you can’t hide.”

NSO has consistently maintained that it thoroughly vets its customers — including the client state’s human rights record — and will only sell after approval from the Israeli government. But the apparent use of Pegasus against Rwandan activists — and dozens of others around the world — raises serious questions about its vetting process and its claim to cancel contracts when misuse is revealed.

In its marketing materials, the company vows to keep outfoxing the defences at the likes of WhatsApp and Apple, pledging to its customers that there will be minimal downtime as tech companies close loopholes.

Apple said in a statement that it provides the most secure platform in the world, delivering updates as quickly as possible to protect iPhones. After WhatsApp raced to close the vulnerability in May, NSO — which often works through affiliates based outside Israel, such as Q Technologies — immediately switched to new methods to deliver the spyware.

At first, that was a persistent pop-up that mimicked a system alert on an iPhone to “carrier settings updates”, according to a person familiar with NSO’s methods. In August, Apple announced a thorough overhaul of its operating system, OS13, designed to enhance privacy. Within days, the person said, NSO was already bragging that it had thwarted those defences too.

Source: https://www.ft.com/content/d9127eae-f99d-11e9-98fd-4d6c20050229