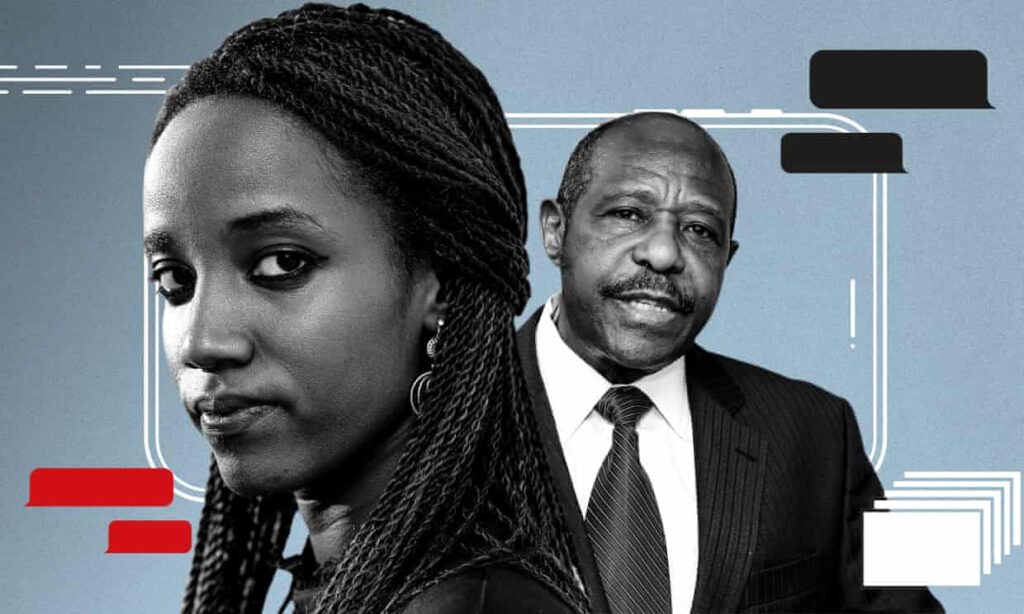

US-Belgian citizen Carine Kanimba has been leading effort to free her father after forced return to Kigali

The American daughter of Paul Rusesabagina, the imprisoned Rwandan activist who inspired the film Hotel Rwanda, has been the victim of a near-constant surveillance campaign, according to a forensic analysis of her mobile phone that found evidence of multiple attacks using NSO Group spyware.

Carine Kanimba, a US-Belgian dual citizen, has been leading her family’s effort to free her father from prison following Rusesabagina’s abduction and forced return to Kigali last year by the government of the Rwandan president, Paul Kagame.

Amnesty International’s forensic analysis found that Kanimba’s phone had been infiltrated since at least January this year.

What is in the Pegasus project data?

It strongly suggests that the Kagame government – which has long been suspected of being a client of the Israeli surveillance firm NSO – has been able to monitor the 28-year-old’s private calls and discussions with US, European and British government officials. A spokesperson for the Rwandan government said the country “does not use this software system … and does not possess this technical capability in any form”.

A phone infected with NSO malware, as Kanimba’s has been, not only gives users of the spyware access to phone calls and messages, but it can also turn a mobile phone into a portable tracking and listening device. In the period before she was alerted to her phone being hacked, Kanimba said she had contacts with the US special presidential envoy for hostage affairs, British MPs, and the UK high commission office in Rwanda – all of which could have been monitored. She also held talks with Baroness Helena Kennedy, a barrister and member of the House of Lords.

The State Department declined to comment.

The forensic evidence suggests the spying began in January – though it may have been earlier – and paused in May while Kanimba was in the US. It resumed again on 14 June, the day she met the Belgian foreign affairs minister, Sophie Wilmès. Sources in the minister’s office said no sensitive information was shared in the meeting.

Rusesabagina is a Belgian national widely credited with saving more than 1,000 people in the Rwandan genocide. He became a vocal critic of Kagame and was living in the US and Belgium until his arrest by the Rwandan government last year. He is facing life in prison after being accused of terror-related charges, including murder and staging attacks in Rwanda. The 67-year-old’s family staunchly deny the allegations.

In an interview with Knack, a journalism partner in the Pegasus project, Kanimba described how the diplomatic effort to have her father released began from the moment she and her family discovered he had been kidnapped, with calls to “every single member of the European parliament and every member of the Belgian parliament” as well as human rights organisations.

“In 1994, during the genocide, the way my father was able to protect people in the hotel was that he made calls every day. With the last working telephone in the hotel,” she said. “And we did the exact same thing.”

News of the hacking campaign will heighten scrutiny of the Rwandan government’s treatment of Rusesabagina at a time when some US lawmakers have pushed for the administration of Joe Biden to put more pressure on Kagame to release him and to protect Rwandans in the US from harassment.

Rwanda has long been suspected of being an end user of NSO malware, with a history of targeting dissidents at home and abroad.

In 2019 at least six dissidents connected to Rwanda were warned by WhatsApp that they had been targeted by spyware made by the NSO in an attack that affected hundreds of users around the world over a two-week period from April to May that year.

Key figures in the Rwandan diaspora, including exiles living in Canada and the US, appear to have been included in a leaked list of persons of interest to NSO clients.

Rusesabagina, who has been referred to as “Africa’s Schindler”, is alleged by family members to have been tortured in the days after his rendition. Rwandan authorities have denied that he was kidnapped or mistreated in custody. His trial has been condemned by human rights groups and has sharpened criticism of Kagame’s nearly three-decade-long hold over Rwanda from key allies in the UK and the US.

In an interview, Anaïse Kanimba, Carine’s sister, said her entire family felt as if they were under constant watch by the Kagame government.

In one case, she said she and her family had reason to suspect their emails were being monitored after her father’s lawyer, Felix Rudakemwa, was searched during a prison visit following a private communication from the family about an affidavit he wanted Rusesabagina to sign that would attest to his allegations of torture. The search, she said, appeared to be focused on finding the affidavit.

“We just assume we are being watched,” Anaïse Kanimba said. “We tell ourselves we have nothing to hide. But this idea of knowing constantly that someone is looking over you, it is really uncomfortable and scary … I hate living with it.”

There is no evidence that Anaïse Kanimba’s phone was hacked.

Vincent Biruta, Rwanda’s minister of foreign affairs, said: “Rwanda does not use this software system … and does not possess this technical capability in any form. These false accusations are part of an ongoing campaign to cause tensions between Rwanda and other countries, and to sow disinformation about Rwanda domestically and internationally.”

NSO denied “false claims” made about the activities of its clients, but said it would “continue to investigate all credible claims of misuse and take appropriate action”. It said in the past it had shut off client access to Pegasus where abuse had been confirmed.

Among the Rwandans that the Pegasus project found were listed in the data as candidates for possible surveillance was David Himbara, an economist who formerly worked for Kagame in Rwanda but later fled and sought protection in Canada. Himbara has questioned claims of stellar economic growth over the years, calling the figures a “fantasy”.

“The lifestyle forced on me is a preoccupation to avoid becoming another victim of Kagame’s death warrant. I do not take personal security for granted even though the distance between Toronto, Canada, where I live, and Kigali, Rwanda, is 11,703km to be precise,” he said.

A forensic analysis of Himbara’s mobile phone by Amnesty International has not found any evidence that it was successfully hacked. It is not clear from leaked records which client country selected Himbara as a potential target.

Fearless international investigations are a core part of Guardian journalism, reaching millions of readers around the world. We believe in chasing the truth and reporting it with integrity and fairness, remaining fiercely independent and free from political or commercial influence. And because we believe in information equality, our work is open for everyone to access. If this is a mission you appreciate, join us today.

From the Snowden revelations to the Cambridge Analytica scandal and our ongoing Covid investigations, in our 200-year history we have exposed high-profile wrongdoings and scrutinised the powerful. We’ve encountered significant risks along the way – from threats to journalist safety to legal menace. But we persevere, because quality investigative reporting has value; it’s helped more people than ever understand what’s happening in our world, why it matters, and how, together, we can demand progress. By collaborating with other news organisations who share our values, our voice is louder and its impact greater.

With no shareholders or billionaire owner, we can set our own agenda and provide trustworthy journalism, offering a counterweight to the spread of misinformation. When it’s never mattered more, we can investigate and challenge without fear or favour. Greater numbers of people can keep track of global events, understand their impact on people and communities, and become inspired to take meaningful action.

Tens of millions have placed their trust in the Guardian’s high-impact journalism since we started publishing 200 years ago, turning to us in moments of crisis, uncertainty, solidarity and hope. More than 1.5 million readers, from 180 countries, have recently taken the step to support us financially.