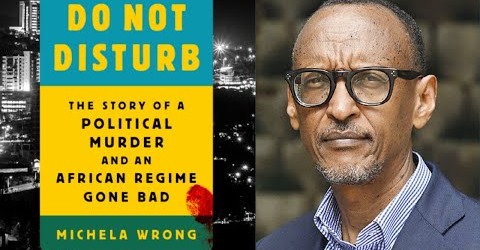

KAMPALA, Uganda (AP) — The new book ” Do Not Disturb ” by British author Michela Wrong questions why some in the international community continue to praise Rwandan President Paul Kagame despite repression in his central African country where he could rule until 2034.

The 63-year-old Kagame’s high profile is due to his role as the leader of rebels who ended Rwanda’s 1994 genocide and rebuilt the country. But critics allege the reconstruction came at the expense of basic freedoms in a country where the president faces no credible opposition and where some opponents have been jailed or forced into exile.

“Obsessed with its dreadful past, the Rwandan population has struck the classic Faustian pact — trading freedom for peace,” Wrong writes. “But most analysts wonder if the deal can survive Kagame’s departure.”

Some critics of the president have died under mysterious circumstances.

The new book’s narrative turns on the death of Col. Patrick Karegeya, a former chief of external intelligence in Rwanda who was a prominent dissident when in 2014 he was strangled in a South African hotel room. Suspicion fell on Rwandan authorities, especially after Kagame told a meeting days later that those “still alive who may be plotting against Rwanda, whoever they are, will pay the price. Whoever it is, it is a matter of time.”

Rwanda’s government denies it had anything to do with Karegeya’s death. But South African authorities issued arrest warrants for two Rwandans suspected of involvement in the killing. Rwanda has not extradited them to face charges.

Later in 2014, South Africa expelled some Rwandan diplomats for their alleged roles in an attack on another dissident. That attack in Johannesburg was the third attempt on the life of former Rwandan army chief Gen. Kayumba Nyamwasa, an associate of Karegeya’s who still heads a prominent opposition group in exile.

Planned attacks on Rwandan dissidents have been reported in countries ranging from neighboring Uganda to Sweden. In 2011, for example, British police warned at least two dissidents that the Rwandan government posed an “imminent threat” to their lives.

After Karegeya was strangled, the killer or killers left a “Do Not Disturb” sign on the door, giving them time to depart the country before detectives and staff discovered his body, according to Wrong, who spent years investigating the killing.

Her book’s title is a metaphor for what Wrong and others see as the unpunished erosion of freedoms in Rwanda. Analysts have long pointed out that Kagame escapes strong criticism from global powers because of lingering guilt over their failure to prevent or stop the genocide that killed some 800,000 ethnic Tutsis and moderate Hutus.

Somber events in Rwanda last week marked 27 years since the killings. In his speech on Wednesday, Kagame said he doesn’t care what the world thinks of him, and accused former government officials in exile of peddling lies motivated by resentment.

“You can tell any lie about me. You’re free to do so. You can pile up tons of blood. It won’t change me,” he said. “Actually, it won’t change this country to be what you want it to be.”

Kagame, who has been Rwanda’s de facto leader since 1994 and its president since 2000, has won praise for restoring order and making advances in economic development and health care.

But Wrong wonders how a leader with a poor human rights record has amassed more honorary degrees than Barack Obama.

“Western funding for his aid-dependent country has not suffered, the admiring articles by foreign journalists have not ceased, sanctions have not been applied, and the invitations to Davos have not dried up,” Wrong writes of Kagame. “Caught in similarly embarrassing situations, would any other African state be shown such indulgence, year in, year out? Russia, Saudi Arabia, and China have certainly not been granted such leniency.”

Johnston Busingye, Rwanda’s justice minister, did not respond to calls seeking comment on the allegations in “Do Not Disturb.” But the book’s focus on Karegeya’s murder has been dismissed in a review published in Rwanda’s government-controlled New Times newspaper, which alleged bias and charged that Wrong “never embraced” Rwanda.

Watchdogs have long cited Rwanda’s poor rights record, noting Kagame’s reelection with nearly 99% of the vote in 2017.

Human Rights Watch said in its 2020 overview of Rwanda that following “years of threats, intimidation, mysterious deaths and high profile, politically motivated trials, few opposition parties remain active or make public comments on government policies.” And Amnesty International in its most recent assessment cited limited space for opposition groups, several cases of enforced disappearances and suspicious deaths in custody including that of Kizito Mihigo, a singer and government critic who was found dead in a police cell last year.

Over the years, Kagame has been challenged by a group of former allies within his Rwandan Patriotic Front party who are fellow Tutsis. That group has splintered as Kagame has cemented his authority, often with devastating consequences for opponents.

But the Rwanda National Congress, the opposition group Karegeya co-founded, is dominated by former members of Rwanda’s ruling party and continues to be outspoken. The group, outlawed back home as a terrorist entity, says it is working for “a united, democratic, and prosperous nation inhabited by free citizens.”

___

This story has been clarified to show that South African authorities issued arrest warrants for two Rwandans suspected of involvement in the killing of Karegeya but they have not been extradited to face trial.