By Howard W. French

DO NOT DISTURB

The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad

By Michela Wrong

In 1996, when I was a Times reporter in Africa, an insurrection broke out in the eastern stretches of a country twice as large as Western Europe and then known as Zaire. Like almost every journalist based in the capital, Kinshasa, in the country’s far west, I struggled to understand how a rebel group that no one had heard of three months earlier could have morphed into the army that would soon march across the country and drive from power its dictator and longstanding American client, Mobutu Sese Seko. Making the story all the stranger, this force was supposedly built from an ethnic community considered marginal even in its home region.

The explanation, which began to emerge only after the “rebellion” was well underway, was that this was no local uprising that had snowballed in popularity and momentum as it swept westward — the cover story backed by American diplomats and initially conveyed unquestioningly by many journalists or depicted as a positive development. It was a carefully disguised invasion by tiny, neighboring, post-genocide Rwanda of a country 90 times its size.

The details of Rwanda’s role in that war, and in a second invasion less than two years later of what by then had been renamed the Democratic Republic of Congo, have been minutely chronicled by historians and specialists of the region, including the millions of deaths. Yet these events, and Rwanda’s continuing economic exploitation and military dominance over the border, have left remarkably little trace on its gilded reputation under the leadership of a man named Paul Kagame, who remains a darling of the international donor community and the Davos crowd.

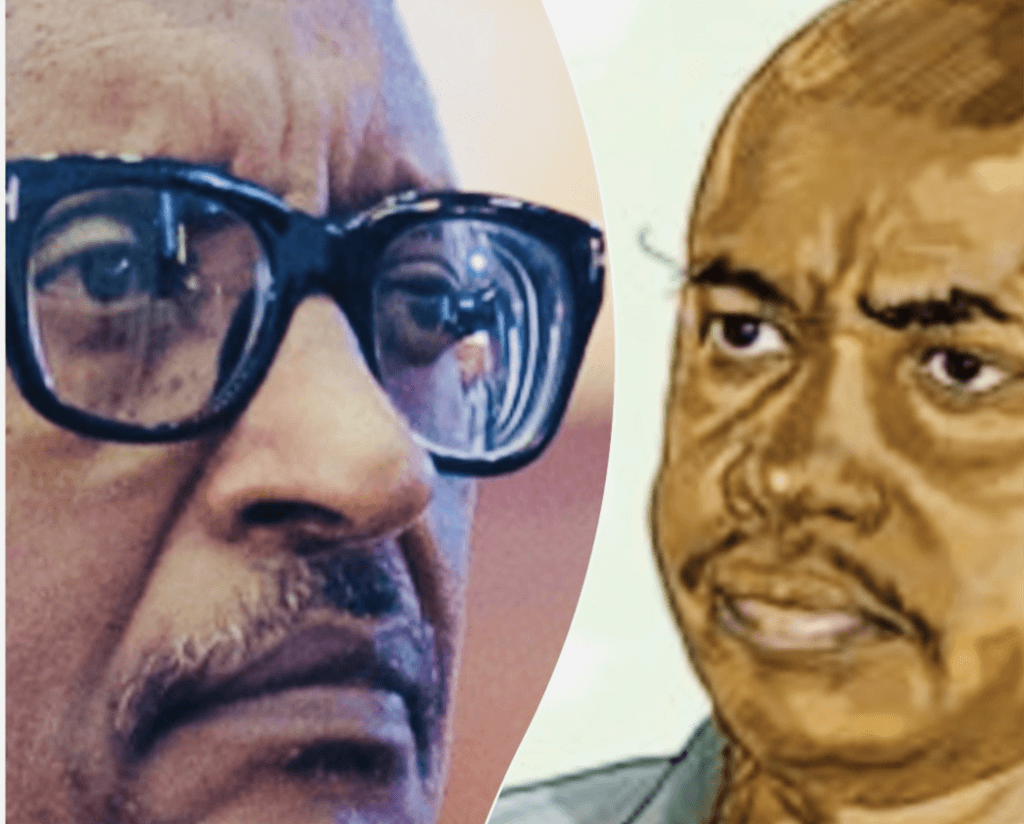

Much the same can be said of Rwanda’s record on human rights, which under Kagame has included a campaign of assassinations targeting his exiled critics. After the most famous of these killings, that of his former spy chief Patrick Karegeya, in 2013, a smiling Kagame told a national prayer breakfast: “Whoever is against our country will not escape our wrath. The person will face consequences.”

“Do Not Disturb: The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad,” by the longtime Africa specialist Michela Wrong, stands out as perhaps the most ambitious attempt yet to tell the dark story of Rwanda and the region’s deeply intertwined tragedies for a general audience. Wrong’s account unfolds on two separate planes. The first is an efficient history of the region. Most readers know little about East Central Africa’s past other than the Rwandan genocide, whose intensity and scale, Wrong notes, rank it among the greatest horrors of the 20th century. But as she makes abundantly clear, that tragedy was but one piece in an interlocking puzzle of ethnic atrocities and military gambits in the region.

This cycle of tragedy began under European rule, when first Germans and then Belgians began formalizing ethnicity in what are now Rwanda and Burundi. The Europeans spun racial fantasies about the colonies’ two main ethnic groups, conjuring distant origins for the often tall and long-legged Tutsi, pastoralists who represented around 14 percent of the population. Tutsi were thus set apart from the shorter, stouter Hutu farmers, who made up 85 percent of the populace. In fact, the two groups share a language and a history of intermarriage, and their identities were traditionally somewhat fluid. Under Belgian rule, the divide was further sharpened with the introduction of ID cards that specified one ethnicity or another, along with that of a third group, a minuscule minority known as the Twa.

The Belgians strongly preferred the admission of Tutsi in modern schools and in the colonial administration. Then, in 1959, three years before independence, as Wrong recounts, the colonizers abruptly reversed course. Fearing Marxist radicalization among the Tutsi, they began to favor the Hutu. As Hutu swept to power in Rwanda’s 1961 elections, scattered Hutu pogroms against the Tutsi broke out. With Belgian approval, the newly empowered Hutu abolished the Tutsi monarchy, traditionally the most important political institution in the land. Threatened and marginalized, Tutsi began pouring into neighboring countries, especially Uganda.

The violence between the two groups escalated monstrously in 1972, with a coup attempt in Burundi, whose ethnic composition mirrors that of Rwanda. Little heed was paid to it at the time, and Wrong mentions it only in passing, but the coup turned into one of the worst ethnic killing sprees of the 20th century. Hundreds of thousands of Hutu were slaughtered by a Tutsi army, and thousands of others streamed into Rwanda, where tales of their persecution further radicalized the Hutu majority. Twenty-two years later, the much larger genocide against Rwandan Tutsi took the world by surprise, but the Burundi coup had set the stage.

Years before, exiled Rwandan Tutsi in Uganda were central to the struggle for power in that country during a long period of violence and misrule under successive dictators, Milton Obote and Idi Amin. When a longtime opposition leader named Yoweri Museveni entered the bush to mount a successful rebellion against Obote, he built his scrappy force from Rwandan Tutsi immigrants and refugees. Among the latter was a stern young man who quickly acquired a fearsome reputation in military intelligence: Paul Kagame.

Early on, this corps of ethnic Tutsi soldiers in Uganda began plotting a return to power in their homeland, and in 1990 they invaded Rwanda. Their force, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (R.P.F.), gained a foothold and engaged in internationally sponsored peace talks with the Hutu-led government until the mysterious 1994 downing of an aircraft carrying the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi — both Hutu. The plane, shot down by unidentified attackers as it approached Kigali, erupted in flames in midair, instantly setting in motion the Rwandan genocide.

The second strand of “Do Not Disturb” is a mixture of Wrong’s highly personal remembrance of the former Rwanda spy chief, Patrick Karegeya, and her dogged investigative reporting on a variety of apparently Rwandan state-sponsored hit jobs, foremost among them Karegeya’s murder in South Africa, where he was first drugged and then garroted. Karegeya had slipped out of Rwanda and into exile after becoming disenchanted with Kagame’s obsession with power and vengeful style.

There is a taut, cinematic quality to Wrong’s account of Karegeya’s killing, and a mournful, hurt tone as well — mournful because Karegeya, a skilled, seductive handler of Western reporters, had been a key source for Wrong while he was in government. The hurt that infuses her story is more subtle, but ultimately more important. It derives from her acknowledgment that she and so many other reporters who covered East Central Africa after the 1994 genocide allowed themselves to be manipulated too easily and too long by their Rwandan sources.

She reproaches herself for not making more of atrocities against the Hutu that occurred even as the genocide was ending, amid a takeover of Rwanda by Kagame’s R.P.F., and later, of the extermination of tens of thousands of mostly civilian Hutu fleeing across Congo. Years later, the U.N. came close to characterizing these killings as crimes of genocide.

Wrong is blunter still when she questions why Western governments have remained so enamored of Kagame, whose elections she suggests are as rigged as those of the most buffoonish African dictators; whose story of supposed economic success is based on crudely falsified data; and who concentrates nearly all power in his hands alone, systematically spying on his own people, heavily suppressing the press and free speech, and jailing or killing anyone who complains too loudly.

“Kagame’s regime, whose deplorable record on human rights abuses at home is beyond debate, has also been caught red-handed attempting the most lurid of assassinations on the soil of foreign allies, not once but many times,” Wrong laments. “Western funding for his aid-dependent country has not suffered, the admiring articles by foreign journalists have not ceased, sanctions have not been applied and the invitations to Davos have not dried up.”

DO NOT DISTURB

The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad

By Michela Wrong

488 pp. PublicAffairs. $32.

Source: https://www.nytimes.com