BY MARTIN FLETCHER

Do Not Disturb” said the sign outside Room 905 of Johannesburg’s Michelangelo Towers hotel on 1 January 2014. When the police finally broke in they found the garrotted body of Patrick Kare-geya, Rwanda’s former head of external security, on the bed. Karegeya had fallen out with the regime he had helped create, and was murdered by a Rwandan hit squad as he helped build an opposition movement in exile.

“Do Not Disturb” is also the sign that has been metaphorically hung on the narrative that Paul Kagame’s Rwandan regime has so assiduously cultivated over the past quarter century – namely that a heroic band of warriors led by Kagame swept in from Uganda to halt the Hutus’ genocide against their fellow Tutsis in 1994, then built a prosperous and harmonious new country on the ruins of the old one.

It is a narrative that the international community, wracked with guilt over its failure to prevent that genocide, has for the most part happily swallowed. Kagame’s regime has faults, it concedes, but it has brought peace and stability to Africa’s highly combustible Great Lakes region and turned tiny, mountainous, landlocked Rwanda into the “Switzerland of Africa”.

Foreign assistance, much of it British, pours into a country that has become an advertisement for the efficacy of international aid. Kagame is welcomed by presidents and prime ministers, hailed by philanthropists and showered with awards. Bill Clinton has called him “one of the greatest leaders of our time”. Tony Blair has praised his “visionary leadership”.

Michela Wrong, the author of acclaimed books on Kenya, Eritrea and Mobutu’s Zaire, dares to differ. She no longer buys Rwanda’s uplifting narrative, although she admits she sometimes did so as a journalist covering the aftermath of the genocide. She has chosen to ignore that “Do Not Disturb” sign and, in an overdue book that takes the injunction as its title, she rips off the regime’s veil of respectability to expose the horrors beneath.

Wrong does so by interviewing former members of a government whose excesses finally became too heinous for them to ignore: men and women who live in fear of assassination despite fleeing their homeland, refuse to communicate by digital means lest they are under surveillance, and met Wrong only in the relative safety of public places – even in Britain.

Indeed, the regime’s tentacles stretch so far that Wrong worked offline while writing the book, hid her laptop in a laundry basket each night, and backed up all her notes in case her London flat was broken into. She says she “never felt so personally at risk”.

Wrong is no apologist for the genocide in which Rwanda’s Hutu majority massacred 800,000 Tutsis – and some moderate Hutus – in 100 frenzied days. She recalls with incredulity how, shortly after the killing ceased, she watched devout Hutus leaving an idyllic church overlooking Lake Kivu one Sunday morning and walk straight past mounds of earth containing the bodies of Tutsi men, women and children who had been slaughtered in that very building.

But, she argues, “genocides do not take place in a vacuum: there is always a context and a build-up”. In this instance it was a history of Tutsi aggression against Hutus and the recent incursion of Kagame’s Tutsi-dominated militia, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), from Uganda into northern Rwanda. The Hutus feared for their own safety, she says. “‘Kill or be killed’ is a motivation most of us can grasp.”

The genocide was triggered by the shooting down of a plane flying Juvénal Habyarimana, Rwanda’s Hutu president, back to the capital, Kigali, from a conference. The RPF accused Hutu extremists of killing Habyarimana because he had made too many concessions in the recent Arusha peace accords. Certainly, the plane’s debris and body parts had scarcely landed on the presidential palace before the slaughter of Tutsis began, suggesting some pre-planning.

But Wrong cites numerous claims by Karegeya and other RPF defectors that Kagame secretly ordered Habyarimana’s assassination to derail a peace process that would have cemented the Hutus’ political power. She also notes that the RPF discouraged any reinforcement of Rwanda’s hapless UN peacekeeping force until it had seized Kigali. Its priority was “capturing power, not saving lives”.

Victors write history, and blaming the RPF for Habyarimana’s assassination quickly became taboo, the equivalent of Holocaust denial. “Entertaining the possibility that, whether through rashness or ruthlessness, the leader routinely labelled in the West as ‘the Man Who Ended the Genocide’ might actually also have started it, would not do.”

Wrong goes on to assert that the RPF secretly slaughtered 30,000 Hutus in the aftermath of the genocide, and that an investigation of that reciprocal massacre was suppressed following intense pressure from Rwanda’s new government. “No tarnishing of the halo would be permitted.”

Worse, Wrong places much of the blame for the two “Congo Wars” that lasted from 1996 to 2003, sucked in a dozen neighbouring countries and caused at least 500,000 deaths, on Kagame’s regime.

Rwanda invaded the neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo to prevent “génocidaires” regrouping in the giant Hutu refugee camps that had sprung up along the border after the RPF seized power. However, it used the conflicts to slaughter thousands more Hutu civilians, remove two DRC presidents and plunder the abundant mineral resources of eastern Congo (taxi drivers call Kigali’s smart new suburbs Merci Congo).

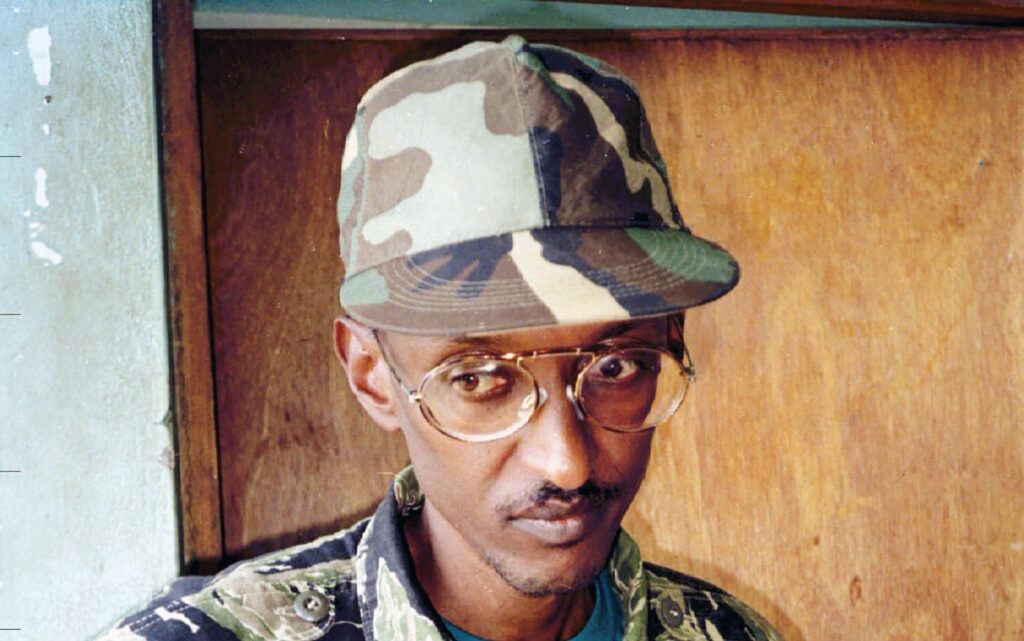

In Wrong’s view, Kagame is the evil genius responsible for so much death and destruction, and her portrait of the Rwandan president is the polar opposite of the saintly one that his government pays Western lobbyists so much to promote.

Born in 1957, the son of Tutsi parents who fled to Uganda to escape Hutu oppression when he was two, Kagame was a sneak who told on his classmates at primary school. He went on to a good secondary school, but turned feral after his father died when he was 15. He was rescued when a young Marxist, Yoweri Museveni, started recruiting Tutsi refugees for his National Resistance Army (NRA), a guerrilla group seeking to overthrow Uganda’s president Milton Obote.

Tall, stick thin and ill-suited to fighting, Kagame became an intelligence officer specialising in the extra-judicial executions of suspected infiltrators, informers and rule-breakers – a task he pursued so zealously that he was dubbed “Pilato” after Pontius Pilate, who ordered Jesus’s execution then denied responsibility. “Contemporaries marvelled at the triviality of the infractions deemed to merit capital punishment,” Wrong writes. A common means of execution was to strike the neck of a kneeling victim with a kafuni – a farmer’s short-handled hoe.

After Museveni toppled Obote in 1985, Kagame joined the new government’s military intelligence department. But over time he and other Tutsis who had fought for Museveni secretly formed the RPF to overthrow Habyarimana’s dictatorial regime in their motherland, Rwanda. In 1990 their charismatic young leader, Fred Rwigyema, was killed in a failed offensive and Kagame, aged 33, succeeded him.

The RPF regrouped under Kagame’s leadership. He recruited child soldiers, purged Rwigyema’s supporters and introduced a draconian disciplinary code that listed 11 capital offences. In 1991 the RPF invaded northern Rwanda, driving thousands of Hutus off their land and into the arms of Hutu militias. The state media fanned hatred of the inyenzi – Tutsi cockroaches. Then Habyarimana’s plane was shot down and the bloodbath began.

Kagame has ruled Rwanda, as vice-president then president, ever since the genocide, and on the face of it he has been astonishingly successful. The country has enjoyed rapid economic growth. Health and education have improved dramatically. Two thirds of its MPs are women. Gacaca, a community justice system, has allowed Hutus to confess their crimes, and official distinctions between Hutus and Tutsis have been banned.

Kigali now looks like a thriving city. The streets are clean and safe. There are no beggars, or street vendors. Plastic bags and smoking in public are banned. Grand-sounding institutions such as the National Electoral Commission, the Office of the Ombudsman, the Rwanda Development Board and the National Institute of Statistics have sprung up “like pristine white mushrooms in the forest”, Wrong writes.

But “no African government curates its public image more assiduously than Rwanda”, she argues, and appearances deceive. Economic statistics are fabricated. The parliament, judiciary and independent media have been neutered. All international NGOs have been banished. Elections are rigged, and Wrong describes a meeting at which Kagame and his associates discussed what percentage of the vote he should award himself.

The reconciliation process is also fake, Wrong contends. The genocide museums and commemorations are designed to remind the Hutus of their guilt. The gacaca trials covered only Hutu crimes, not those of the RPF. Hutus are given prominent political positions for cosmetic purposes only. “Genuine ethnic reconciliation would undermine a regime that depends for its survival on the concept of perpetual war, requiring the existence of a never-to-be-vanquished foe,” Wrong writes.

As for Kagame himself, Wrong portrays him as a paranoid, ruthless and half-mad control freak with a tell-tale vein on his temple that throbs when he is angry. He kicks, beats and whips senior commanders in front of their subordinates. He personally eavesdrops on military communications to monitor his armed forces. He micro-manages his aides’ personal lives, telling one to divorce a wife he deemed insufficiently “Rwandan”. Senior officials cannot travel abroad without his permission.

Nobody is safe from the “roiling, inexplicable fury” within him. Patrick Karegeya grew up with Kagame, fought beside him and did his dirty work. Their wives were friends. Their children played together. But when he lost faith in the regime and sought to resign, he was first imprisoned and later forced to take what Rwandans call the “subway” – an underground escape route out of the country. Then he was murdered in South Africa.

The book is littered with similar examples of former allies, critics and outright opponents being demonised, imprisoned, exiled and killed on foreign soil. In 2011 Scotland Yard warned three Rwandan exiles in London that they were targets. In September last year Paul Rusesabagina, who gave more than 1,200 Tutsis refuge in his Kigali hotel in 1994 but later became a fierce opponent of Kagame, was lured from his exile in Texas and bundled on to a private jet to Rwanda. The hero of the movie Hotel Rwanda is now being tried for terrorism.

A disaffected RPF luminary quoted Kagame saying: “Those wazungus [white people] make noise, but over time they forget it.” He was right. There is abundant evidence of Kagame’s atrocities, much of it chronicled in this powerful, compelling and meticulously researched book. But the West has little interest in ostracising an African leader who offers it stability, expiation of guilt, a showcase for foreign aid and regular contributions to African peacekeeping operations.

Thus Britain continues to give Kagame’s regime £54m a year. Thus his police state will host the next Commonwealth summit. And thus, says Wrong, “Western funding for his aid-dependent country has not suffered, the admiring articles by foreign journalists have not ceased, sanctions have not been applied, and the invitations to Davos have not dried up.”

Do Not Disturb: The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad

Michela Wrong

Fourth Estate, 512pp, £20

Martin Fletcher is a former foreign editor of the Times and a New Statesman magazine contributing writer and online columnist.

Source: https://www.newstatesman.com/