She escaped the genocide in Rwanda. Now, 27 years later, she can’t escape its politics. In yoga classes, in downtown D.C. dance clubs, in her spreadsheet of the city’s newest restaurants that she and her 20-something friends frequent, Anaïse Kanimba found normalcy. And anonymity.

“Here in D.C., I am my authentic self,” she said. “It is my home now.”

In Washington, she isn’t the terrified orphan the world wept for in an Oscar-nominated movie. She isn’t the toddler hiding from a massacre while surviving on chicken feed after her parents were slaughtered. She isn’t the target of Rwandan spies hunting her famous family in Belgium. She isn’t Hutu or Tutsi.

She’s a Georgetown University graduate, class of ’15. She’s a smiling face on LinkedIn, a Digital Solutions Senior Associate.

Until last week, when she was thrown back into a familiar fear and terror, watching her adoptive father stand trial, accused of terrorism by the home nation where the story of his heroism unfolded.

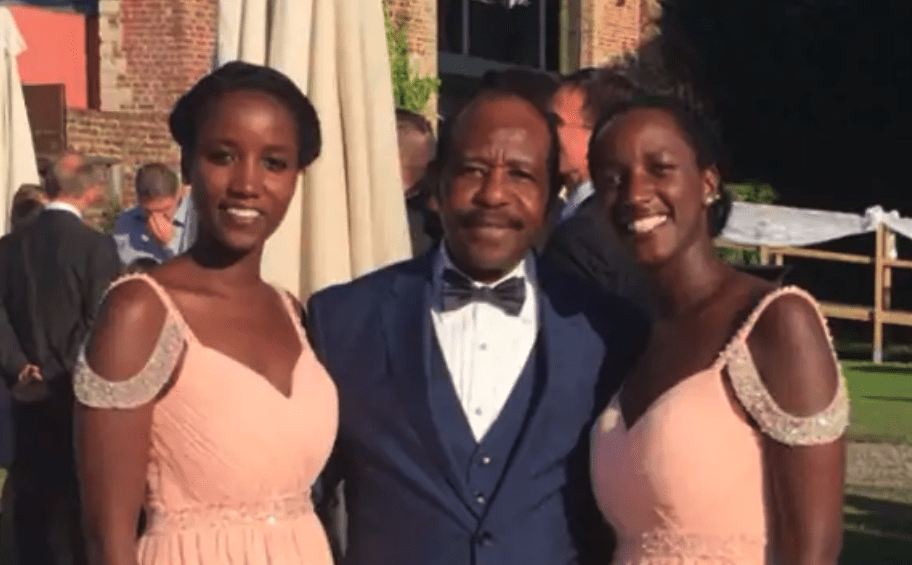

Kanimba, 29, is now speaking out loudly and emphatically as the daughter of Paul Rusesabagina, manager of the place known as the Hotel Rwanda. She is fighting for his release after an astonishing plot last year that whisked him out of his safe haven in San Antonio to Dubai, then bound and blindfolded on a private plane — according to the lawsuit she filed in December against the Greek aviation company that provided the plane — back to Kigali, where he was imprisoned and is now on trial.

“There’s nothing else that I could be doing right now but working to get him back,” she said. “It is my destiny . . . I was brought to Washington, D.C., for some reason, and this must be it.”

Kanimba became known to the world in 2004 when the movie “Hotel Rwanda” rattled the Western world into understanding the enormity of the Rwandan genocide 10 years earlier. It’s told through the story of Rusesabagina, the manager of a four-star hotel in the Rwandan capital of Kigali, who sheltered about 1,200 people behind the hotel’s walls while at least 800,000 were massacred across the nation.

Two of those killed were Kanimba’s parents. Biologically, Kanimba is Rusesabagina’s niece. At the end of the film, as the hotelier, his wife and son are rescued and about to be evacuated to Belgium, they find the orphaned Kanimba and her younger sister in a refugee camp and adopt them.

Kanimba was just 2 years old during the war and remembers none of it.

“It’s a weird feeling not to have those memories,” she said from her D.C. home. “On the one hand, it allowed me to move forward and to live my life. But I think my parents were 28 or 29 when they were killed — my age now. I wish I could remember his face and her face.”

She didn’t know she was adopted by the Rusesabaginas until she was 6 years old. They told her what she needed to know, but didn’t cloud her childhood with the brutal stories of slaughter in the streets. She learned most of that when she was 12 and saw the movie.

“I hated the movie,” she said. It was the first time she had pictures in her mind of Kigali, the massacre, the brutality.

She’s learned more about that time since then.

“I learned in the last couple of years that my dad died in the very first week or so of the genocide,” she said. “My mother died four or five weeks in. And I’ve heard stories of how we survived, eating chicken feed when we were in hiding.”

This is the closest she can get to Rwanda. She’s worked for nongovernmental organizations that get her on the African continent, but because of her father’s continued activism in Rwanda and the enemies he’s made, she wouldn’t be safe visiting.

The film made Rusesabagina the world’s most famous Rwandan. He used his platform — nights with Hollywood stars, the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom, audiences yearning to understand the nation’s conflict — to continue advocating for human rights and peace inside his home country and criticizing Paul Kagame, the rebel leader who became president.

While Kagame became the West’s darling, receiving massive amounts of aid, Rusesabagina said the president began skewing toward authoritarianism. The former hotelier became an opposition leader in exile and a thorn in Kagame’s side.

Then their home in Belgium was ransacked, prompting their move to the United States, Kanimba said. Her parents settled in San Antonio, where they have some Rwandan friends, and found peace and safety in a gated community.

Last summer, Rusesabagina received an invitation to speak with faith leaders abroad. Kanimba and her sister helped their dad, who is 66 and recently battled cancer, find a good flight with limited layovers, good coronavirus protocols and a quick return.

But after he was scheduled to land in Dubai, he never returned their texts. The next time the family heard from him was from a prison in Kigali, arrested on charges of terrorism.

The Rwandan government said they had a warrant accusing him of inciting violence during a 2018 speech when he said: “The time for us has come to use any means possible to bring about change. . . . It is time to attempt our last resort.”

Some of the armed subgroups of his followers did launch attacks on Rwandans that left several people dead. But the international community has not drawn a line directly from Rusesabagina to the violence, and has resoundingly condemned his arrest. Human Rights Watch called it an “enforced disappearance.”

In America, 37 members of Congress signed a letter strongly urging Kagame to free Rusesabagina. Kanimba has done much of the legwork on that campaign after it became clear last fall that President Donald Trump, while on a spree freeing political prisoners across the globe, would not help a fellow hotelier.

The trial began live-streaming last week. Kanimba was horrified to see her dad — always an impeccable dresser — in such debilitated condition.

“Seeing him in the pink. Prisoners in Rwanda wear pink . . . and he lost about 40 pounds,” she said. “I thought: ‘That’s not him. That’s not my father.’ ”

The family believes their last hope is President Biden. If Biden shows support for Rusesabagina, they believe Kagame will let him go. Biden hasn’t spoken publicly about the situation, and Kanimba is lobbying him to do so.

In the movie, Rusesabagina is shown using his smarts and connections to keep holding off the rebels. At one point, he tells them that Americans have devices to monitor their behavior. “America is watching,” he tells them.

Kanimba borrowed from that when she marshaled the support from American lawmakers: “He has to know Congress is watching Rwanda. America is watching.”

By Petula Dvorak

Twitter: @petulad