JOHANNESBURG – King Goodwill Zwelithini, monarch of South Africa’s large amaZulu ethnic group, has died, ending his five-decade reign through the darkest years of the racist apartheid system, the democratization of the 1990s, and the ups and downs of modern South Africa.

The royal house confirmed his death early Friday, saying he had been hospitalized with blood sugar problems several weeks earlier. He was 72.

Zwelithini was more than a figurehead, though he held no formal power. He made history as the longest-serving head of the Zulu Kingdom, which is estimated to number between 10 and 12 million, most of them in South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal province.

In a statement, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa said, “His Majesty will be remembered as a much-loved, visionary monarch who made an important contribution to cultural identity, national unity and economic development in KwaZulu-Natal and through this, to the development of our country as a whole.”

Pitika Ntuli is a member of the larger amaZulu community, and is also an artist, poet and historian. He says the king touched the lives of many South Africans — not just his own ethnic group.

“His presence loomed large over the nation. He was very, very vocal about the issues that he really believed in, that affected his people, affected the province and also affected the country,” he told VOA. “And he was generally a very open, welcoming, supportive person. That’s why when you would go over to his royal kraal, the people who visit him would be coming from the Indian continent, from all walks of life. Even within South Africa itself, he had a very good and powerful following.”

And, Ntuli added, he also had a wonderful sense of humor — a side of the king not many people got to see.

Modern ruler

Zwelithini is the most recent in a long line of Zulu leaders, who pride themselves on their skill as warriors. Perhaps the most famous of them was King Shaka, who ruled in the early 1800s and is famed for his military prowess. He is often credited with inventing the strategies that, after his death, enabled the Zulu fighters to hold their own against invading British soldiers.

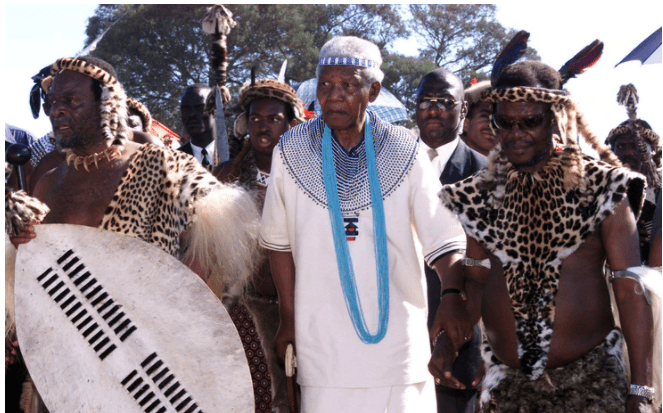

Zwelithini was a more modern ruler. Although he donned the customary garb, danced the elaborate dances and sang the deeply moving songs of his people, he notably toned down some of the rhetoric. In his later years, he focused not on the vitality of the Zulu people, but on their humanity. Last year, he spoke about what Ramaphosa has described as South Africa’s “second pandemic” — the nation’s astoundingly high rate of violence against girls and women.

“The killing of my daughters,” he said to a crowd that had gathered for the annual reed dance, “has made me ashamed to be king of the Zulus. I ask myself, ’how can I be leader of such a cruel nation?’ AmaZulu, what happened to the humanity you are known for?”

Controversies

The king’s reign was not entirely smooth. He occasionally spoke against the ruling African National Congress, and in earlier years raised eyebrows for his positive comments about the apartheid regime.

He also came under criticism for his government-funded lifestyle of elaborate palaces, luxury cars and expensive parties and vacations in a nation beset by inequality and high unemployment. The government budgeted nearly $5 million for him this year.

Ntuli defended the king, saying he also used his largesse to benefit his people — for example, giving nine farms to the Ntuli people. And, to critics who complained about the king’s comfortable life, he countered: Isn’t Queen Elizabeth comfortable? Why shouldn’t an African king be, as well?

“It’s not as if he was taking these things and just simply enjoying it himself, without having to share what it is, in terms of the duties that he had to perform for the people all around him,” Ntuli said.

Future of throne

Zwelithini’s line will continue. He is survived by six wives. Local media estimates that he has between 28 and 32 children.

It’s not clear which one of them will inherit the throne, as the king’s successor is customarily only chosen after his death. Custom dictates that the king’s “great wife” — in this case, his third wife, Queen MaNtofombi Dlamini — gets preference. Her eldest son, Prince Misuzulu Zulu, is the eldest surviving son of the king and a strong candidate to succeed him.

But all that can wait. Today, many South Africans — not just the Zulu people, but also the Xhosa, the Bapedi, the Tswana, the Ndebele, the Basotho, the Venda, the Tsonga, the Swazi, the San, the Cape Colored, the South Asians, the Afrikaaners, the English and the many others who make the Rainbow Nation such a vibrant, colorful place — are saying, “Hamba Kahle.”

That means, in isiXhosa, “go well.”