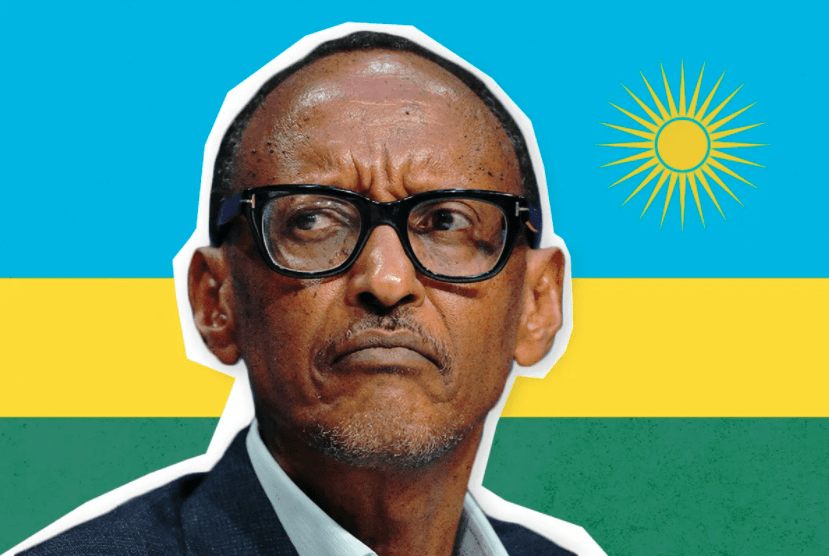

On July 3, 2020 the investigating chamber of the Paris Court of Appeal upheld the December 21, 2018 decision of the investigating judges Herbaut and Poux, dismissing, for lack of sufficient evidence, the case regarding the missile attack, on April 6, 1994, against the plane of Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana. This decision meant the abandonment of proceedings against nine suspects close to the current Rwandan President, Paul Kagame. The terrorist act of April 6 heralded the resumption of the Rwandan civil war, the genocide of the Tutsi and the seizure of power by the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). Subsequently, it also deeply destabilized the entire Great Lakes region. While the civil parties announced an appeal in the Court of Cassation and certain voices1 wish to see other avenues of investigation explored, this decision marks the provisional end of a legal saga that has lasted twenty-two years. The outcome is disappointing since it amounts to the conclusion that there was a crime without perpetrators.

Concluding that the persons under investigation cannot be referred to the Assize (Trial) Court because of insufficient evidence, the decisions of the investigating judges and of the investigating chamber do not really establish any judicial truth. There are no other suspects and there will probably be no adversarial proceedings before a substantive court. However, the “court of history” can and must continue its work. The purpose of this article is to gather the facts that we have been able to collect on this case; it shows the abundant evidence pointing to the RPF as the perpetrator of the attack.

Our approach will be technical and exclusively based on facts, some of which are disputed, others established beyond a reasonable doubt. Unlike others who have commented on this affair, we do not want to suggest that political considerations interfered in the decisions of the French courts. On the contrary, we have every reason to believe that the investigating magistrates, the prosecution and the investigating chamber did their job in a professional manner. We will conclude that, from the technical, legal point of view, their decisions are understandable.

We look at three themes that have been central to the pre-trial investigations: the place from which the missiles were fired, the origin of the missiles, and the perpetrators of the attack. We draw on many judicial and extrajudicial sources. Our judicial references concern mainly the judgment of the Court of Appeals investigating chamber, which essentially reproduces the terms of the prosecutor’s request to dismiss the case and the investigating judges’ order of dismissal. We will summarize here the data from thousands of pages of information accumulated during the past 25 years. By necessity the themes analysed are not discussed in detail.

1 For example R. Doridant, “Génocide contre les Tutsis du Rwanda : rideau sur un attentat”, Survie, July 1, 2020.

Before examining the facts, it should be noted that scenarios were presented that were expected to be taken seriously but don’t deserve it. This is especially the case for documents produced by Belgian, French and American intelligence services which, during the weeks and months after the attack, made assumptions based on thin evidence. A recently released instance illustrating the problem well is a “particular file” of the DGSE (French Foreign Intelligence Service) of September 22, 1994, that was revealed, without the slightest critical sense, by an “investigation unit” of Radio France and Mediapart on February 6, 2019. The DGSE formulates what it itself calls a “hypothesis”, based on a single statement of an unidentified person, that would “tend to designate Colonels Bagosora (…) and Serubuga (…) as the main sponsors of the attack”. The note constantly uses the conditional and contains several factual errors. Its lack of seriousness is obvious from reading the appendix entitled “Main members of the ‘Zero Network’”. This list repeats in full and in the same order that which we had published two years

Missile Firing Location

Two types of sources indicate the location from where the missiles were fired: eyewitness accounts and technical expertise. Two hypotheses were considered: the Masaka area to the south-east of the Kanombe military domain and two places, close to each other, on the edge of the military domain itself.3 The importance of identifying the firing zone is considerable, because it is unlikely that the RPF would have carried out the attack from the military domain or its immediate surroundings, but it could have accessed the area of Masaka. However, even if the missiles were fired from Masaka, this in itself would not demonstrate the guilt of the RPF. Yet the RPF did everything to eliminate the possibility of this firing zone, both through the Mutsinzi report (see below) and during the French investigations.

Let us first consider the witness statements of the time. They are relevant for two reasons. First, delivered immediately after the event, they are “fresh”, therefore more reliable than those recalled many years later, and not “polluted” by subsequent information. Further they date from a period when no one yet realized the importance of this information, as the RPF was not suspected at the time of having committed the attack.

On April 13, 1994, a week after the incident, Major Daniel Daubresse told the Belgian military auditor that he “saw, looking eastward, ascending from right to left, a projectile propelled by a red-orange flame (…) Direction of fire between 190800 and 190820 from south-south-east to north-north-west, maximum distance 5 km from our location. The minimum distance very difficult to appreciate, of the order of 1 km”. Heard the same day, Lieutenant-Colonel Massimo Pasuch said “I fully agree with the statement of Major Daubresse”. Daubresse and Pasuch were together in Pasuch’s residence, which was located at the northeastern end of the Kanombe military domain, and whose bay window, through which they saw the departure of the missile(s), overlooked the east, that is to say the valley of Masaka. This is 2-3 km from the house.4 Based on the statements of Pasuch and Corporal Mathieu Gerlache, who was at the airport’s old control tower, Gendarme Warrant Officer Guy Artiges concludes that “we can assume that the shooting took place in the immediate vicinity of the [Masaka] farm” (Pro Justitia 25 May 1994). Corporal Pascal Voituron, who was at the airport, refers to “two red dots that came from bottom to top and from right to left when looking at the end of the runway, but I didn’t hear the sound of the firing that seemed to have come from afar. Plus or minus five kilometres from the point of departure to the plane” (Pro Justitia 30 May 1994), which corresponds to the vicinity of Masaka valley. Also before the Belgian military auditor, Jacques Gashoke (a Tutsi witness speaking very critically about Colonel Bagosora, whom he accuses “of being one of the chiefs of the death squad”), who was located below the Kanombe town hall, testifies that “The luminous points [of the missiles] came from the direction of Masaka hill” (Pro Justitia 1st January 1995)5 . In 1995, the Belgian military auditors continued to maintain that the missiles were fired from the Farm in the Masaka Valley.

Other accounts from the time point in the same direction. Jean-Luc Habyarimana, son of the president killed in the crash, described to Jeune Afrique “the light trajectories of rockets from Massaka [sic], the hill that planes fly over, on landing, just before the residence”.7 In June, Belgian journalist Colette Braeckman wrote in Le Soir: “It also appears – and we saw it on the spot – that the shot came from the locality Massaka [sic], located behind the Kanombe military camp”.8 In October 1994, we personally met three witnesses in Masaka, two Rwandans and a European priest, who affirmed that the missiles had been fired from the vicinity of Masaka Farm.

This is confirmed by two investigations by the prosecutor’s office of the ICTR. Based on three sources within the RPF, the “Hourigan Report” in 1997 mentions a unit called the “Network” which, among other things, was responsible for the attack.9 Heard by the French judges, an investigator from the Hourigan team confirms that two sources inside the RPF indicated that the missiles had been fired from Masaka, where they had been transported concealed in a truck.10 A second report, this time from the “Special Investigations” team also designates Masaka as the location of the shootings.11 It must also be noted that for more than ten years, the Masaka valley was unanimously considered as the starting point of the missile attack, a fact that was only contested when the accusations against the RPF became clearer.

Other witness statements were subsequently collected in the context of three investigations, that of the Rwandan Government Mutsinzi Commission, that of the French investigating judges and that of the Special Investigations team of the ICTR’s prosecutor’s office. It is interesting to note that even five of the eight statements taken from the report of the Rwandan Mutsinzi Commission maintain Masaka as the location of the shooting.13 Of the 13 direct witnesses cited by the French investigating judge, nine designate the Masaka area, while three indicate the surroundings of Kanombe. The thirteenth witness, Mathieu Gerlache, presented as designating the Kanombe camp, is incompletely cited, since he specified that “from this place, you could see the runway but not the FAR camp, the latter being below (the horizon)”. However, the Masaka valley is in prolongation of his line of vision and Gerlache is unable to estimate the distance between where he was (the old control tower) and the missile launch point.14 Two more sources cited in the judgment, the Hourigan report of the ICTR and that of Amadou Deme, investigator in his team, note that three RPF officers claim that the missiles were fired from Masaka.15 At the time we were finalising this paper, a Rwandan eyewitness who lived on Masaka hill and requested anonymity for security reasons (he lives in Rwanda), confirmed to us that he and two other persons who were with him saw and heard the launch of the missiles from the surroundings of the “Farm” in Masaka valley.

The vast majority of eyewitnesses therefore point to the Masaka valley as the launching point for the attack. 16 According to several sources, both from the French judicial inquiry and from the ICTR special investigations team, the missiles were stored, prior to the attack, in the house of a family close to the RPF located near Masaka (Ndera hill is mentioned twice).

Why were Masaka’s witnesses not interviewed? In the report of the so-called independent Mutzinzi committee, the statements of the “population of the hills near the site of the attack” are dealt with in a few lines: “Due to lack of minimum technical knowledge, their stories are unclear about the nature of the phenomena observed and sometimes even implausible. Some of these witnesses confuse what they have learned from others with what they have seen for themselves, so that their statements are not of great interest”. 17 However, the Mutsinzi report is crafted to show that the missiles came from the Kanombe military camp, and any information to the contrary must therefore be excluded. It is surprising that, like the Mutsinzi committee, the French investigating judges did not interrogate witnesses in Masaka. This raises the question of how and by whom they were guided in the choice of people to hear. In this regard, it should be noted that nine of the twelve witnesses cited by the expert report also testified before the Mutsinzi committee, and that only these nine were actually heard by the experts.

While most eyewitnesses locate the launch of the missiles in the Masaka area, an expert study carried out at the request of the investigating judges considers another firing point more likely. The experts started from the hypothesis of a direct, “normal” approach of the plane (i.e. straight onto the runway), but they do not exclude that an alteration in the trajectory could have been made after the first shot. The expert report says this: “This tilt to the left followed by an extinction of the (plane’s) lights could indicate that, seeing the light of the first missile, the crew then attempted an avoidance manoeuver which seems logical from the point of view of a pilot, consisting of shutting off his lights for stealth purposes and suddenly changing his trajectory”. 18 Likewise, “an alteration of the flight path may have been made by the pilots if they saw the first shot, the one that missed its target. It is in the logic of a military pilot to deviate laterally his trajectory and possibly make a sudden change in altitude”. 19 The possibility of an avoidance manoeuvre was the subject of a supplementary expert’s report which concluded that there had been none20 and that, even in the case of an avoidance procedure, the missiles could not have been fired from Masaka. However, the supplementary report does not say where the missiles would been fired from if there had been evasion by the aircraft.21 The experts’ report also mentions a letter from the pilot, who expressed his fear of a threat from surface-to-air missiles and considered low and high altitude departure and arrival strategies. Based on radio communications with the control tower, however, the experts are of the opinion that the flight approach was straightforward, normal, in relation to its point of origin.

Conclusion of the experts: even if two firing positions located in Masaka “offered the highest probability of success of all the shooting positions studied”, the experts point to two locations in or near the Kanombe military domain, “where the probability of a successful attack appeared sufficient so that of the two missiles fired, one of them could hit the plane”. These two positions are found near the cemetery, on the edge of the domain. 23 “The missiles could nevertheless have been fired from a more extensive zone, of the order of a hundred meters or more”, which would locate the firing point on the outside of the Kanombe domain and in any case in a place far from the military camp.24 The prosecutor’s request for dismissal adds that these conclusions were consistent with the statements of Massimo Pasuch and Daniel Daubresse, while we have seen that they locate the departure of the missiles in the Masaka area.

In any case, the expert’s report does not make a final or decisive decision. It concludes that the Kanombe site “is the most probable firing zone”. 25 Moreover, the judgment classifies the examination of the crash site and aircraft wreckage as “late and incomplete” and observes that “the sites visited had changed considerably in 16 years”. 26 In addition, data from a supplementary report on acoustics cannot be conclusive, since the tests were carried out at La Ferté Saint Aubin in the Loiret (France), on flat terrain very different from the Rwandan hills and based on sound sources different from those of SA-16 missiles.

A cautious approach to the experts’ report is called for in light of the uncertain nature of a number of the technical data (possible avoidance procedure, abnormal approach, condition of the plane’s debris), but above all in light of the contradictions with most eyewitness testimony. However, neither the order of dismissal nor the judgment of the investigating chamber attempt to reconcile the data based on the technical expertise and eyewitness statements. In identical terms, under the heading, “The direct witnesses of facts and the confrontation of these testimonies with expert reports”28, they simply recall that eight witnesses indicated “the direction of Masaka” against three29 indicating the “surroundings of Kanombe”. However, there is no “confrontation” of the witness statements with the expert report. It is therefore not clear why the decisions give precedence to the expert report over the direct witness statements. The judges do not explain why the probative value of one piece of evidence would outweigh another which, moreover, comes from several sources.

The Missiles

There is considerable evidence showing that the RPF had a surface-to-air capability. In the overview of the RPF weapons mentioned in his reconnaissance report of August 1993, General Dallaire, who would later command the UNAMIR force, includes “a number of eastern bloc short range AD missiles”. In his memoirs, he writes that “the RPF had anti-aircraft guns, mortars and possibly surface-to-air missiles in the CND, which was only four kilometres from the airport”.31 Much earlier, the RPF had shown that it had surface-to-air weapons and knew how to handle them. In October 1990 and February 1993, they shot down a reconnaissance plane and two helicopters of the Rwandan army. The conviction that the RPF had such systems, including in Kigali after the installation of their battalion at the CND, was widely shared. For that reason, an internal Air France memo required pilots to observe a perimeter of 1 kilometer around the CND building during take-off and landing, a requirement also decreed by the RPF for other reasons.32 In a letter sent on February 28, 1994 to a pilot friend, Jean-Pierre Minaberry, captain of the presidential aircraft, expressed concern over the RPF’s possession of surface-to-air missiles, citing SA-7 and SA-16. He asked him questions about the safe altitude to adopt and said he was studying departures and arrivals from low and high altitude to minimize the danger (see above).

Two weeks after the plane attack, refugees displaced by the fighting discovered two missile launchers in the Masaka valley. The army was notified of this discovery and Lieutenant Munyaneza33 wrote down the serial numbers found on the tubes, without realizing what type of missile it was.

The markings on the tubes show that they are SA-16 missiles:

According to Lieutenant Munyaneza, the launchers were empty and were therefore used.35 In the course of the French investigation, a representative of the Moscow military prosecutor’s office confirmed that “the missile launchers bearing serial numbers 04814 and 04835 had indeed been manufactured in the former USSR in 1987 and that they had been part of a lot of 40 units sold to the Ugandan government in a from State to State sale”. Strangely, under the title “The dispute concerning the place and the date of discovery of the missile launchers”, the French judgment casts doubt on the discovery at Masaka exclusively on the basis of findings of the Mutsinzi report.36 The fact that the launchers have disappeared and that, apart from the document drafted by Lieutenant Munyaneza and a photo of one of the launchers, there is no physical evidence, obviously poses a problem.

In addition to this discovery, two SA-16 missiles can be linked to the RPF. On May 22, 1991, the French military assistance mission in Kigali reports an SA-16 missile recovered by the FAR from the RPF on the 18th May on the front. The note indicates that the Rwandan army is prepared to hand it over to the defence attaché.

The tube has the following markings:

9Π322-1-01

04-87 04924

9M313-1

04-87 04924

C

LOD.COMP

On September 20, 2016, a “strictly confidential” report from the UN MONUSCO mission (United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in DR Congo) notes that in August the FARDC (Armed Forces of the DRC) recovered parts of a surface-to-air missile from the Rwandan rebel movement FDLR (Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda). According to the Group of UN Experts on the Congo, this missile was taken in September 1998 from the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA) during an operation of the Rwanda Liberation Army (ALIR), predecessor of the FDLR.39 The tube has the following markings that show it is an SA-16:

9Π322-1-01

04-87

04860

9M313-1

04-87 04860

C

LOD.COMP

The individual numbers of these missiles which can unmistakably be linked to the RPF (04860 and 04924) are obviously of the same series as those discovered in Masaka valley (04814 and 04835). More importantly, all four come from Ugandan stocks. In September 2018, we were able to obtain photos of Ugandan Army inventories and the four missiles mentioned above clearly come from these stocks, as shown in the following table:

The serial numbers in bold are those related to the RPF, the others are those in the Ugandan stocks40 having serial numbers similar to those linked to the RPF (the fact that the latter no longer appear in the Ugandan lists show that they have been transferred to another user).

As an example, we reproduce here one of the 53 photos of the Ugandan inventories in our possession:

These data clearly show that the four identified missiles were in the hands of the RPF and that they came from Ugandan stocks. The judgment of the investigating chamber notes that “the Ugandan origin of these missile launchers, a country in which the RPF was formed and where all its cadres were trained, reinforces the hypothesis of an attack committed by this organization. Several testimonies also indicated that Uganda was the main supplier of RPF weapons” (p. 30). The judgement also recalls that the technical experts considered it a very high probability that the SA-16 was the weapon of the attack. The only doubts about the discovery of the missile launchers mentioned by the judges came from the Mutsinzi report, so there is no need to dwell on it.

Finally, the judgement only accepts the indications that the RPF had SA-16 missiles (p. 31). It is, therefore, surprising that neither the order of dismissal, nor the judgment of the investigating chamber concluded that the missiles used in the attack were in the possession of the RPF and it was they who fired them. Finally, it should be noted that the RPF was ready to act at the time of the attack, while there was total confusion on the government side. On the one hand, according to several sources within the RPF, around 7 p.m. on April 6th the contingent from the RPF at the CND was ordered to be on “stand-by one”, which meant that its units had to be combat ready and in the trenches around the building.41 On the other hand, according to several witnesses present on the ground, the offensive by the RPF’s main force in the north began very early in the morning of April 7th, particularly in the Kisaro, Rukomo, Kagitumba and Nyabishongwezi areas. This large-scale operation launched in record time could not have been achieved without prior knowledge and preparation.

The judgment briefly considers whether the FAR had a surface-to-air capability. It appears that they considered acquiring them, but everything indicates that they did not do so.43 The only doubts on this subject come again from the Mutsinzi report. The judges also cite a document from UNAMIR made public by Human Rights Watch, showing that the FAR held an unknown number of SA-7 surface-to-air missiles. Apart from the fact that the systems used in the attack were SA-16, this document has no value. British Captain Sean Moorhouse, an intelligence officer with UNAMIR-II and supposedly the source for Human Rights Watch, told us: “I did not draw up the list of weapons suspected to be in the possession of the FAR. I inherited it. UNAMIR was such a dysfunctional entity that I don’t even know where the list came from. There were no means available to verify the accuracy (or otherwise) of this list of weapons. This was made clear to Human Rights Watch at the time. (…) It was not possible to say with any certainty who had shot the aircraft or from where. (…) Rumours and speculations were all I had to go on”.

Because nothing justifies it, the judgement does not follow the trail of surface-to-air missiles held by the FAR.

The Shooters

Several testimonies report meetings at the RPF headquarters in Mulindi, where the attack was allegedly discussed and the decision to shoot down the plane made. Other witnesses, some of whom are former RPF soldiers, implicate the rebel movement, mainly on the basis of hearsay. We do not analyse these statements for two reasons. First, they are questionable, sometimes contradictory and there are doubts whether these witnesses could have seen or heard what they say they observed. Then and above all, these statements are not important since, if the RPF committed the attack, in light of the practices and structures of this organization it is inconceivable that an act of this magnitude would have been decided at lower levels. It is at the top, and concretely at the level of Paul Kagame himself, that such a resolution would have been discussed and taken.

On the other hand, witness statements on the direct perpetrators of the attack and their way of proceeding are numerous and, apart from details, consistent. With regard to the shooting team, nine witnesses cited in the judgment of the investigating chamber name Franck Nziza as one of the shooters (of the second shot that brought down the plane), while five cite Eric Hakizimana as the other shooter. Five witnesses mention Didier Mazimpaka as the driver and three Patiano Ntambara as the team’s close guard. We are particularly interested in Nziza who, according to our Ugandan sources, while an NCO serviceman with the rank of Warrant Officer C1 of the NRA (National Resistance Army, name of the Ugandan army at the time), was reportedly trained in surface-to-air missile use in the former Soviet Union.45 The ICTR Special Investigations team report quotes a source confirming that Nziza received training in the handling of missiles.46 Another revealing indication involves Nziza. According to several sources (one of which is cited in the judgment, p. 25), during a celebration organized in Matimba in 2000, songs thanked the RPF for promoting an officer who had shot down the plane. This officer was Franck Nziza and, as soon as his name was mentioned, the security services put an end to the singing. 47 In light of all these indications, it is understandable that the examining magistrates were particularly interested in Nziza, going so far as to summon him, together with James Kabarebe, at the time Rwandan Minister of Defence, for a confrontation with a witness scheduled in Paris on December 14, 2017. 48

The route of the missiles from the RPF headquarters at Mulindi to the CND in Kigali and then to the launching site is also fairly well documented. If the accounts of Mulindi’s transport to Kigali differ on certain details, they converge on the observation that weapons were hidden under shipments of firewood. As for the transfer of the missiles from the CND to the location where they were used, several witnesses claim that they were stored in a house belonging to a family of RPF sympathizers in Ndera, not far from Masaka valley. In addition, several RPF messages claiming the attack were intercepted by the FAR in the hours following the attack. However, their authenticity has been disputed on the basis of a single testimony from FAR radio operator Richard Mugenzi. Before the Mutsinzi Committee he evokes the fabrication of false messages to be disseminated in FAR units to galvanize them against the RPF. According to him, Lieutenant-Colonel Anatole Nsengiyumva brought him texts already written and gave him the order to transcribe them by hand as if they were real messages intercepted on the frequencies of the RPF.49 However, when he testified before the ICTR and Judge Bruguière, the same Richard Mugenzi confirmed having himself intercepted a message from the RPF announcing the success of the attack by the “reinforced squad”. 50 In a report dated 7 April 1994, Captain Apedo, a Togolese military observer with UNAMIR at Camp Kigali, writes that “RGF (Rwanda Government Forces, reference to FAR) major said they monitored RPF communication which stated ‘target is hit’”. 51

Finally, it should be noted that during the first years following the attack, it was openly recognized and even claimed with pride in RPF circles or close to it. Jean Marie Micombero, a former RPF officer, summed up these feelings well: “This attack is now a defence secret while for several years many people knew and spoke openly about the operation against Ikinani (Habyarimana). It really didn’t become a secret until after the issuing of Judge Bruguière’s warrants”.

Doubts of the Judges

Despite the accumulation of evidence implicating the RPF in the attack, the French judges found weaknesses in the demonstration. The judgment notes the absence of material findings on the identification of the missiles and the firing point. They observe that “too many inaccuracies or contradictions in the witness statements remain as to the places, dates and circumstances of their discovery” (p. 51). On the issue of where the missiles were fired from, the judgment notes that “the experts have favoured the Kanombe site as the most probable firing zone, that is to say the cemetery and the bottom of the cemetery, an area that can however be extended to the east and south by around a hundred meters or more” (p. 51). While the judges say that “the investigations carried out suggested, though with significant doubt due to contrary testimonies, that the RPA had SA-16 missiles in their possession”, they believe that “no concrete evidence has come to confirm these affirmations” (p. 52). The judgment even suggests, on the basis of highly questionable data (the Mutsinzi report and a report from UNAMIR, cf. supra) and without excluding this hypothesis, that the FAR could have possessed a surface-to-air missile capacity (p. 53). On the basis of contradictions between certain witness statements and the supposed lack of credibility of other statements, the judges concluded that it is not proven that the RPF transported missiles from Mulindi to Kigali (p. 53-54). Likewise, statements accusing RPF leaders for having sponsored the attack are said to be “for some [of them] indirect, or often contradictory” (p. 56). The judgment notes “the presence of hearsay in Rwandan culture” (p. 47), a phenomenon which makes certain statements suspect.53 Finally, concerning the report drawn up in October 2003 by the ICTR’s Special Investigations team, the judgment considers that it contains “no new determining elements” (p. 56). Conclusion: “There is not sufficient evidence to charge anyone with committing the crime which is the subject of the referral, no matter how the offense is qualified”.

The dismissal order is therefore confirmed. The investigating judges had already concluded that “The accumulation [of witness statements] cannot constitute serious and concordant charges allowing the referral of the indicted persons to the Assize Court” (Order, p. 46). From a judicial point of view this decision is understandable, since doubt benefits the accused and the defence would not have hesitated to raise such doubts before the trial court. Indeed, both the investigating magistrates and the prosecution must assess the chances of obtaining a conviction.

Conclusion

The judgment observes that the investigation “took place in atypical conditions which do not facilitate the manifestation of truth” (p. 13). It rejects certain leads and briefly presents, without studying it, that of the Hutu extremists, a thesis based exclusively on the “findings” of the Mutsinzi commission (p. 14-15). It does not therefore come to conclusions on the innocence or the guilt of either side. The attitude of both parties to the conflict regarding establishing the truth about the attack has been very different. On the one hand, as soon as it was set up, the interim government asked UNAMIR to conduct an international investigation. While General Dallaire accepted this in principle and exchanges took place on its practical modalities, it did not materialise. Likewise, the dignitaries of the former regime detained at the ICTR have repeatedly insisted that an investigation be carried out into the attack. For its part, the RPF has always opposed it. In a letter he wrote to us on November 2, 1995 from Nairobi, Sixbert Musangamfura, who was chief of intelligence in Kigali until August 1995, points out that “a posteriori, the RPF had an interest in a careful investigation being carried out if it was not involved in the attack. We asked the VicePresident of the Republic and Minister of Defense [Paul Kagame] to facilitate the establishment of a national or international commission of inquiry to elucidate the facts. He replied that the country had other priorities and that Habyarimana is just one of the hundreds of thousands killed during the genocide”. Musangamfura adds that Colonel Kayumba Nyamwasa, head of the DMI (Directorate of Military Intelligence), who had seized and classified all documents relating to the attack (telegrams from the Ministry of Defense, military intelligence reports, airport duty report and book, sound elements …), told him he had them burnt. We have seen that it was only thirteen years later, to blow smoke in the face of the investigation conducted by judge Bruguière, that a biased investigation was carried out by the Mutsinzi Committee. However, the partial nature and some fraudulent aspects of this investigation rather confirm the guilt of the RPF. This refusal to conduct a serious investigation was accompanied by the sabotage of the discovery of the truth, in particular by the elimination of embarrassing witnesses, resulting in a long list of murdered or disappeared people (Théoneste Lizinde, Seth Sendashonga, Léandre Ndayire, Patrick Karegeya, Emile Gafirita, Chrysostome Ntirugiribambe, Augustin Cyiza).

Not only has the RPF always opposed an investigation but, when faced with the reality of the French judicial inquiry, they employed a strategy with the same objective. They preferred the non-establishment of their guilt (by the dismissal of the case) rather than the establishment of their innocence (by an acquittal before the Assize Court, the trial court). This finding is corroborated by the fact that, despite the accusations made by the Mutsinzi committee, they did not ask that the investigation be extended to the other side. On the contrary, thanks to the doubt that was raised they wanted to end the proceedings as soon as possible. The strategy of the suspects and their lawyers attest to their fear that a finding of guilt could be the outcome of the legal process if it were followed through to the end.54 Yet “as long as there is any doubt, it will make deniers happy”55 which logically could not be the RPF’s objective if they knew they were innocent.

While we said we understand the order of dismissal and its confirmation on appeal, decisions in the reverse sense could have been taken. In fact, on the one hand, they attach decisive importance to the technical expertise, while it is not conclusive, a fact recognised by the judgment: “due to a number of points of coherence, the experts favoured the Kanombe site as the most probable” (p. 51). Probable but not certain, and to this are added doubts raised even by the ballistics report (possible approach of the aircraft not normal, but at high or low altitude, possible avoidance procedure, alteration of aircraft debris sixteen years after the incident). It is therefore false to say, as Libération did on January 11, 2012 on the front page and in large print, that the experts had established the truth “irrefutably”. The great weight given to the experts’ evaluations of the evidence is undoubtedly partly due to its technical character, which gives it an air of infallibility, even if it is based on certain presumptions and contradicted by several other elements in the file. On the other hand, while some witness statements are questionable or contradictory on points of detail, they are at the same time remarkably consistent on the decision, at the top of the RPF, to carry out the attack, the origin of the missiles, their transfer from Mulindi to Kigali and then to the firing zone, and finally on the identity of those who fired the shots. It is also striking that many sources within the RPF claim responsibility for the attack, while no source within the ex-FAR or the government of the day does. In a column published in Le Monde, a Collective criticized us for having written56 that a number of indications point at the RPF as the perpetrator of the attack.57 In light of what our article shows, their accusation is flimsy, to say the least. Let us consider:

– The missiles used in the attack came from Ugandan stocks and were in the possession of the RPF;

– The RPF had shown in the past that it possessed the capacity to handle surface-to-air missiles;

– The missiles were transported from the RPF headquarters in Mulindi to the CND in Kigali and from there to the area from where they were fired;

– At least one of the suspects in the missile firings, Franck Nziza, had been trained in the handling of surface-to-air missiles when he was in the Ugandan army;

– Many sources within the RPF claim responsibility for the attack;

– The main argument in favour of the RPF’s innocence, the experts report, is less conclusive and decisive that often claimed;

– The RPF has consistently opposed any serious investigation and has disappeared or assassinated potential witnesses;

– There is no evidence to implicate the other party to the conflict, who in addition have always insisted that an investigation be conducted.

Since a bundle of evidence therefore indeed designates the RPF as the perpetrator of the attack, a judicial determination of the case would have been preferable. Without such a determination doubts will remain, and there will continue to be believers and nonbelievers.

The RPF did it IOB Working Paper

The RPF did it. A fresh look at the 1994 plane attack that ignited genocide in Rwanda

Filip Reyntjens

Working Papers are published under the responsibility of the IOB Research Commission, without external review process. This paper has been vetted by Marijke Verpoorten, chair of the Research Commission.

Comments on this Working Paper are invited.

Institute of Development Policy

Postal address: Prinsstraat 13 B-2000 Antwerpen Belgium

Visiting address:

Lange Sint-Annastraat 7 B-2000 Antwerpen Belgium

Tel: +32 (0)3 265 57 70

Fax: +32 (0)3 265 57 71 e-mail: iob@uantwerp.be http://www.uantwerp.be/iob

WORKING PAPER / 2020.05

ISSN 2294-8643

The RPF did it. A fresh look at the 1994 plane attack that ignited genocide in Rwanda

Filip Reyntjens* October 2020

*Institute of Development Policy, University of Antwerp

filip.reyntjens@uantwerpen.be