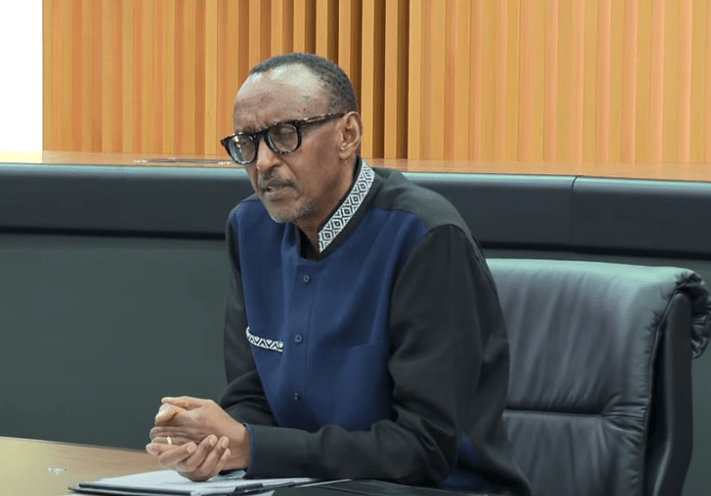

For years, UN investigators secretly compiled evidence that implicated Rwandan President Paul Kagame and other high-level officials in mass killings before, during and after the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

The explosive evidence came from Tutsi soldiers who broke with the regime and risked their lives to expose what they knew. Their sworn testimony to a UN court contradicted the dominant story about the country’s brutal descent into violence, which depicted Kagame and his RPF as the country’s saviours.

Despite the testimonies, a UN war crimes tribunal — on the recommendation of the United States — never prosecuted Kagame and his commanders. Now, for the first time, a significant portion of the UN evidence is revealed, in redacted form.

The redacted witness testimonies are available here.

In early July 1994, as the genocide in Rwanda was nearing its end, Christophe, whose real name and location are being withheld for safety reasons, was recruited by the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF).

Christophe, a medical student before the war, was assigned to care for wounded RPF soldiers in Masaka, a neighborhood in the southeast of Rwanda’s capital, Kigali.

The RPF was on the brink of winning the war. It was the culmination of a bloody campaign that began in 1990 when its forces invaded Rwanda from their base in Uganda, where their Tutsi families had been forced into exile for three decades.

Their struggle for political power in Rwanda took a drastic turn on 6 April 1994, when a plane carrying Rwanda’s then president Juvénal Habyarimana, a Hutu, was shot down in Kigali, killing everyone aboard, and abruptly ending a power-sharing deal that was supposed to end three-and-a-half years of violence. The plane attack set off a killing spree that left hundreds of thousands of Tutsis dead, mostly at the hands of their Hutu countrymen. By mid-July, the RPF had routed the former Hutu government, and purportedly put an end to the massacres.

From his battle clinic in Masaka, though, Christophe saw that the killings were continuing. “People were disappearing,” he recently told the Mail & Guardian. Many of the new recruits Christophe treated began to share sobering details about what they were being ordered to do to Hutu civilians — men, women and children who had no apparent connection to the killing of Tutsis. These Hutus were being arrested in different areas of the capital by RPF officials, they said, and brought to a nearby orphanage called Sainte Agathe, where they were summarily executed.

The young recruits told Christophe that they were being forced by their RPF superiors to tie up civilians and kill them with hammers and hoes, before burning the victims on site and burying their ashes. It was grisly, traumatising work conducted daily, they told him.

Many of the soldiers asked Christophe to provide them with a sick leave note to avoid taking part in the killings. “They didn’t want to kill anybody,” he said. One of the recruits told Christophe that over a mere five days, more than 6 000 people were slaughtered at the orphanage.

In late July, the RPF sent Christophe and thousands of other recruits to Gabiro, a military training camp located in eastern Rwanda, on the edge of the vast wilderness that made up Akagera National Park. The rebel army had established a base there earlier in the war, and it was off limits to international nongovernmental organisations, United Nations personnel, and journalists.

The RPF had begun to recruit Hutu men, promising them safety if they joined the RPF cause. Many heeded the call. But at Gabiro, Christophe saw that these new Hutu recruits had been deceived. Instead of receiving training, on arrival they were screened by military intelligence agents, taken to a field and shot.

Even Tutsi recruits from Congo, Burundi and Uganda, whom military intelligence considered disloyal or suspect, were disappearing, he said.

Even more chilling, though, were the truckloads of Hutu civilians Christophe witnessed arriving in another part of the camp, in an area he could see from a distance. Every day, for months on end, he said, RPF soldiers killed these Hutus and then burned the bodies. Backhoes — which Christophe referred to by their brand name, Caterpillar — worked day and night burying their remains. “You could see the trucks, you could see the smoke. You could smell burning flesh,” Christophe told M&G. “All those lorries were bringing people to be killed. I saw the Caterpillar and could hear it. They were doing it in a very professional way.”

As the massacres continued, Christophe became worried that as a witness he, too, could be a target. Some soldiers, traumatised by what they were forced to do, tried to escape Gabiro. But they were caught and executed, he said. To his relief, in April 1995, he was transferred out of Gabiro, and a week later, he fled Rwanda and never returned.

Several years after leaving, Christophe began speaking to investigators from the UN International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). The tribunal, set up in the aftermath of the genocide, was tasked with prosecuting the most serious crimes committed in 1994. Publicly, the tribunal focused exclusively on prosecuting high-level Hutu figures suspected of organising and committing genocide against Tutsis. But privately, a clandestine entity within the ICTR, known as the Special Investigations Unit (SIU), gathered evidence of crimes committed by the RPF. By 2003, investigators at the SIU had recruited hundreds of sources, with dozens giving sworn statements.

According to a summary report submitted to the ICTR’s chief prosecutor in 2003, the SIU’s investigative team had gathered explosive evidence against the RPF. Numerous witnesses corroborated Christophe’s testimony that the RPF had engaged in massacres of Hutu civilians in Gabiro and elsewhere before, during, and after the genocide. Sources testified to the SIU that the RPF was behind the 6 April 1994 attack on Habyarimana’s plane.

Former soldiers even told investigators that RPF commandos undertook false flag operations. Some commandos, operating in civilian clothes, had allegedly infiltrated Hutu militias, known as Interahamwe, to incite even more killings of Tutsis in a bid to further demonise the Hutu regime and bolster the RPF’s moral authority in the eyes of the international community.

In the report, UN investigators listed potential RPF targets for indictment, including President Paul Kagame himself. But when the tribunal officially wound down in 2015, the more than 60 individuals who were convicted and jailed for genocide and other war crimes were all linked to the former Hutu-led regime. Not a single indictment of the RPF was ever issued by the UN; all evidence of RPF wrongdoing was effectively buried.

Christophe met with investigators three times, and provided a written, sworn testimony to the tribunal, but for nearly two decades, his testimony, together with that of dozens of other RPF soldiers who witnessed RPF crimes, have remained sealed in the tribunal’s archive.

In this exclusive report, the Mail & Guardian is publishing 31 documents based on testimonies the witnesses provided to UN investigators. The documents were leaked to M&G by various sources with extensive experience at the tribunal. The witness statements, which contain identifying information, have been redacted by the tribunal and by the M&G to protect the informants’ privacy and safety.

The informants who testified against the RPF to the tribunal faced serious risks, and some were kidnapped, according to the investigators. However, it is widely believed by our sources that the unredacted witness statements are already in the possession of the RPF. One statement is unredacted because the witness died in 2010.

Since 1994, many human rights researchers, journalists, academics and legal experts at the ICTR have contended that the crimes committed by the RPF were not comparable in nature, scope, or organisation to the Hutu-led atrocities against Tutsis.

The Rwandan government has asserted that any crimes committed by members of the RPF were only acts of revenge that have already been tried by the competent Rwandan authorities.

These testimonies, which include gruesome details about RPF massacres — often from soldiers who directly participated in the killings — challenge that understanding. Although these accounts do not in any way prove culpability, they may constitute prima facie evidence needed for indictments.

Taken as a whole, the evidence collected by the SIU suggests that RPF killings were not a reaction to the killing of Tutsis but instead were highly organised and strategic in nature. If proven by a court, the RPF not only played a seminal role in triggering the genocide by shooting down Habyarimana’s plane; its senior members also engaged in widespread, targeted massacres of civilians before, during and after the genocide.

Many of the RPF commanders implicated in the crimes documented by the SIU have held, or continue to hold, important positions in the Rwandan government and military. Kagame, who was the leader of the RPF at the time of the 1994 genocide, has been the president of Rwanda since 2000 and remains a close ally of the United States.

General Patrick Nyamvumba, who was head of the Gabiro training camp, served as the head of the Rwandan military from 2013 until 2019, and before that, from 2009 until 2013, as commander of Unamid, the joint UN-Africa Union peacekeeping force in Sudan. He was also minister of internal security until April 2020.

Lieutenant Colonel James Kabarebe, whom witnesses cited for his leading role in massacres in northern Rwanda and in planning the assassination of Habyarimana, was Rwanda’s minister of defence from 2010 until 2018 and remains a senior adviser to Kagame. General Kayumba Nyamwasa, who was head of the RPF’s military intelligence during the genocide, is alleged to have conceived and organised the RPF infiltration of Hutu militia and the mass killings of Hutu civilians throughout Rwanda. Nyamwasa fled the country in 2010 and is a major figure in the Rwandan opposition in exile.

Neither the RPF, the Rwandan president’s office, the Rwandan Media High Council, nor Nyamwasa responded when asked for comment on the documents. On Twitter, Yolande Makolo, an adviser to Kagame, dismissed an M&G query about the documents and called the questions “ridiculous”.

Filip Reyntjens, a Belgian political scientist who has spent decades studying Rwanda and provided expert testimony to the ICTR, said the RPF’s legitimacy is based on saving Tutsis and stopping the genocide, and that any critical examination of its real record would undermine that official narrative.

“The legitimacy of the RPF is in large part based on its image as representing and defending the victims of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi. They are the ‘good guys.’ Any evidence that points to the RPF committing massive crimes or having a role in shooting down the presidential plane, an act that sparked the genocide, challenges that legitimacy, which is why they have to fight it tooth and nail,” Reyntjens told the M&G.

Christophe, whose statements and interviews with the M&G are corroborated by other witnesses who offered similar testimony, said he believed the killings that he witnessed at Gabiro could not have been carried out as revenge for the crimes individual Hutus committed during the genocide.

The killings by the RPF went on “for too long [ and] were too programmed and well organised,” to amount to retaliation, he said.

The Gabiro massacres

Other witnesses bolstered Christopher’s account, providing testimony that the RPF began killing at Gabiro in April 1994, shortly after Habyarimana was assassinated. Speaking to investigators in French, one witness, a former soldier who joined the RPF in 1992, told investigators that displaced Hutu civilians from villages in northern Rwanda were brought to Gabiro aboard tractor-trailer trucks, and left at a residential complex called the House of Habyarimana, 3km from the military camp.

The intelligence officer selected the intelligence staff and instructors to execute the people brought by trucks … The soldiers tied their elbows behind their backs, and one by one, made them walk to a ‘grave site’ above the House of Habyarimana, where they were shot … These summary executions were done day and night between four and five weeks that I was there … By the end of April, early May, after two weeks of summary executions, the smell of corpses reached the Gabiro camp. Two bulldozers were used to bury the bodies.

The witness said he participated in burning bodies using a mixture of oil and gasoline to turn the corpses into ash in a forest near another training camp called Gako. The soldier in question said a lieutenant called Silas Gasana who was in charge of security for a man referred to as “PC-Afandi”, oversaw the killings at Gabiro. “PC-Afandi” is a military moniker for Kagame, according to former members of the RPF who were separately interviewed on the topic.

The witness told investigators that Gasana was in communication with Nyamvumba, who at the time was the operations commander and chief instructor at Gabiro.

Another former RPF soldier who was sent to Gabiro in mid-April 1994 told the tribunal:

Many trucks came from different regions around the camp. Recruits who went to get firewood could see these trucks pass. In two instances, while I was about a kilometre from our camp looking for wood, I personally observed these trucks. They were tractor-trailers, or semi-trailers. The vehicles had 18 or 24 wheels with no licence plates. They drove past me, very close. They were full of men, women, children and old people. They were brought to an area near the houses of the former head of state, near the Gabiro airstrip, and massacred.

The witness said the victims were from northern areas of Rwanda and were killed so that Tutsi refugees living in Uganda could acquire their land. The testimony highlighted the RPF’s alleged practice of falsely blaming Hutus for atrocities they didn’t commit.

The main objective of these massacres … was to prepare the land and pastures for the people who had been [Tutsi] refugees in Uganda and who were repatriated. Until today, anyone [that is Hutus] who might think of living there without having returned from Uganda, would run the risk of being accused of being an Interahamwe.

Other witnesses spoke of killings at the military camp on the edge of the park. A former intelligence officer described Gabiro as a main “killing hub”.

The officer took part in operations in Giti, in northern Rwanda, from April 1994, in an area where no Tutsis had been killed during the genocide. Despite the commune being safe for Tutsis, RPF special forces killed up to 3 000 Hutus there, he testified.

Between two and three thousand [civilians] were executed in the commune of Giti, and were buried in mass graves and latrines. Thousands of other victims were brought to Gabiro. It was a killing hub, above all isolated and near Akagera Park … At one point, victims from areas surrounding Giti began to arrive in military trucks, on their way to Gabiro, where they were simply eliminated.

Massacres in northern Rwanda before the Genocide

Anumber of former RPF soldiers testified that Hutu civilians were attacked prior to the genocide, in particular in northern Rwanda.

One soldier said that as soon as the RPF seized an area — which he referred to as a “liberated zone” — Hutus living there were systematically slaughtered.

The [RPF] was convinced that Hutus were uncontrollable, so it was better to get rid of them. That’s why a systematic ethnic cleansing was organised in these ‘liberated zones’. Two methods were used to achieve this goal. The RPF would organise murderous attacks, where hundreds of Hutu peasants were killed. The survivors would then flee and empty the zone. The RPF would also spread rumours about imminent attacks, a tactic that would cause peasants to flee.

A RPF soldier who served in the northwestern region near Ruhengeri testified that in 1993, the purpose of his unit was to “kill the enemy and bury or burn their corpses.” The soldier said he was part of this unit until August 1994.

The goal of our group was to kill Hutus. That included women and children. We killed many people, maybe 100 000. Our unit killed on average between 150 and 200 people a day. People were killed with a cord [around their neck], a plastic bag [over their head], a hammer, a knife, or with traditional weapons [machete, panga]. The bodies were then put into mass graves or sometimes burned.

In their summary report, SIU investigators cited a host of methods used by the RPF to kill victims, including strangling them with cords, smothering them with bags, pouring burning plastic on their skin, and hacking Rwandans with hoes and bayonets.

The RPF infiltration of Interahamwe

According to three testimonies, RPF soldiers wore uniforms seized from the [Hutu government] Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR) and used government-issued weapons to commit crimes in false flag operations. One former RPF soldier described the logic behind RPF attacks against civilians in a demilitarised zone before the genocide:

The most important task was to destabilise the regime by killing civilians. Once they [the RPF] withdrew, they spread the rumour that the [Habyarimana] regime was incapable of protecting civilians.

These RPF commandos, known as “technicians”, embedded within the Interahamwe, were stationed in zones controlled by the Interahamwe and participated in killing civilians at road blocks during the genocide, according to the witness. “They even killed Tutsis,” said one former RPF soldier.

Another former RPF soldier, who was based in Kigali from April to July 1994, witnessed similar events. He told investigators that RPF commandos dressed up as government soldiers or disguised themselves as members of the Interahamwe, and used machetes to kill Tutsi civilians at roadblocks. The witness claimed the RPF deployed more than two battalions of these commandos in the capital alone.

They checked IDs [and] killed people by machete exactly like the Interahamwe, so no one would be suspicious.

False flag operations continued until well after the end of the genocide, according to various testimonies.

Triggering the bloodbath

Early on in the genocide, it was widely believed that Hutu hardliners were responsible for shooting down the president’s plane in a bid to hold on to power. The belief in this hypothesis remains widespread. However, RPF informants told the tribunal that the RPF planned and executed the attack on Habyarimana’s plane.

A number of former RPF soldiers said the RPF unearthed secret weapons caches immediately preceding the 6 April attack to prepare for battle. Sources told the SIU that Kagame and his senior commanders held three meetings to prepare the attack. In the summary report, UN investigators “confirmed” the existence of a RPF team in charge of surface-to-air missiles, which were allegedly transported to Kigali from the RPF’s military headquarters in northern Rwanda, near the Ugandan border. SIU documents named the individuals who allegedly brought the missiles into the capital, hid them and fired them on April 6, 1994, and included Kagame and Nyamwasa as potential targets for indictment.

One witness testified that before the attack on the plane, on the night of 6 April, RPF soldiers were told to get ready:

On 6 April 1994 at 19:00 hours, the order was received from Kayonga to be on ‘stand-by one’. This meant to be in full battle dress and ready for an attack. All the companies moved outside the camp into the trenches … At approximately 20:30 hours, I saw the president’s plane crash.

Another witness was later told by an intelligence agent that the RPF was indeed behind the plane attack:

He told me that it was the RPF who shot down Habyarimana’s plane. When he realised his indiscretion, he threatened me with reprisals if I didn’t keep it to myself.

The testimonies support the work of an earlier investigation undertaken in 1997 by the ICTR, by a lawyer called Michael Hourigan, who collected evidence indicating that the RPF was behind the plane attack. Louise Arbour, the UN tribunal’s chief prosecutor at the time, shut down the probe and told Hourigan that she did not have the mandate to investigate acts of terror, according to a number of interviews Hourigan gave after he quit his job in frustration with her decision. In later years, Arbour told The Globe and Mail newspaper that Kagame’s government blocked efforts to investigate RPF crimes and the tribunal did not have the resources to carry out such an inquiry safely.

In 2000, Carla Del Ponte, who took over after Arbour, made it clear she intended to indict the RPF. “For me, a victim is a victim, a crime falling within my mandate as the [Rwanda tribunal’s] prosecutor is a crime, irrespective of the identity or ethnicity or the political ideas of the person who committed the said crimes,” she said in a speech in 2002. “If it was Kagame who had shot down the plane, then Kagame would have been the person most responsible for the genocide,” she later said at a symposium organised by the French Senate.

But in 2003, the US government warned Del Ponte that if she went ahead with her plans to indict the RPF, she would be fired, according to her memoir. Within a few months of a tense meeting she had with Pierre-Richard Prosper — then US Ambassador for War Crimes Issues, who had served as a prosecutor for the ICTR from 1996 to 1998 — Del Ponte was removed from the ICTR.

According to this leaked memo, dated 2003, Prosper struck a deal with the court to transfer jurisdiction for prosecuting RPF crimes — and evidence of RPF crimes collected by UN investigators — from the UN tribunal to the Rwandan government.

Prosper is currently a partner at Arent Fox, where he advises and represents the Rwandan government in international arbitration and litigation, according to the firm’s website . Prosper did not respond to our request for comment.

Hassan Jallow, Del Ponte’s successor, who oversaw the court’s prosecution until it closed in 2015, was ultimately unwilling to indict the RPF. In 2005, he defended the ICTR’s decision not to prosecute the RPF, writing that Kagame’s army had “waged a war of liberation and defeated the Hutu government of the day, putting an end to genocide.”

Since 1994, several other UN agencies have investigated RPF attacks on Hutu civilians, both inside Rwanda and in neighbouring countries. These reports were also suppressed, or became the focus of vigorous denials from Kigali. Although they address other alleged crimes of the RPF, they corroborate the SIU’s general findings that the RPF committed widespread, targeted crimes against Hutus.

Robert Gersony, a US consultant, was hired by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees in the summer of 1994 to assess whether it was safe for Hutu refugees who had fled Rwanda to neighbouring countries to return home. Gersony’s 1994 report was never officially made public, but according a version that was leaked in 2010, investigators concluded that the RPF killing of Hutus during the genocide was “systematic” and resulted in the death of tens of thousands of civilians.

A senior official of the UN’s peacekeeping force in Rwanda said Gersony gave a verbal briefing in which he put forward evidence that the RPF had carried out a “calculated, pre-planned and systematic genocide against the Hutus.”

The UN Mapping Report, which investigated abuses committed by pro-Rwandan forces in the DRC between March 1993 and June 2003, concluded that attacks against Hutu civilians in that country, “if proven before a competent court, could be characterised as crimes of genocide.”

Despite the Mapping Report findings, the RPF has never been prosecuted for its alleged crimes in the DRC. Human rights advocates such as Denis Mukwege, a Congolese doctor who won the Nobel peace prize in 2018 for treating women who have experienced sexual violence, have repeatedly called on the international community to set up a tribunal to try all perpetrators of atrocities and end the culture of impunity in the DRC. Nevertheless, the UN High Commission for Human Rights, whose investigators authored the 550-page Mapping Report, has chosen to keep its database of suspected perpetrators confidential.

Efforts by France to investigate the shooting down of Habyarimana’s plane have similarly failed to establish any accountability. In 2006, after a lengthy investigation, a French judge issued arrest warrants for several RPF officials in connection with the assassination of the Rwandan president, a move that triggered a diplomatic row between Kigali and Paris.

In December 2018, a court dismissed the case against the RPF, citing insufficient evidence to proceed to a trial and, on 3 July this year, an appeals court in Paris confirmed the decision and agreed not to reopen an investigation.

Researchers have recently attempted to estimate the number of victims of violence, both Tutsi and Hutu. In January, the Journal of Genocide Research published several studies that estimated between 500 000 to 600 000 Tutsis were killed during the genocide, and between 400 000 and 550 000 Hutus lost their lives in the 1990s.

Marijke Verpoorten, an academic at the University of Antwerp, says it remains impossible to establish a reliable death toll of the killings of Hutus. Instead, she attempts to estimate how many Hutu lives were lost in the 1990s, either as a direct result of violence, or indirectly, after the rapid spread of contagious diseases in refugee camps, and the dire war conditions. She arrives at a “guesstimate” of 542 000, although admits there is a very large uncertainty interval.

Yet only one ethnic group has been internationally recognised as victims. Inside Rwanda, community-based gacaca courts tried more than 1.2-million alleged perpetrators of the Tutsi genocide. An official genocide survivor fund does not recognise Hutus who were killed, even if they lost their lives trying to protect Tutsis. Hutus are not allowed to publicly grieve their loved ones or request justice for RPF crimes in Rwanda.

After formally closing, the ICTR became a residual tribunal — now called the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (MICT) — and continues to search for high-profile, alleged Hutu génocidaires. In May, French police arrested 87-year-old Félicien Kabuga, who had lived in hiding for 26 years. He stands accused of financing the genocide against Tutsis by funding an extremist radio station. Kabuga has denied the allegations and is currently in the Hague awaiting a trial.

The MICT did not respond when asked for comment on prosecuting RPF officials.

Subscribe to the M&G for R2 a month

These are unprecedented times, and the role of media to tell and record the story of South Africa as it develops is more important than ever.

The Mail & Guardian is a proud news publisher with roots stretching back 35 years, and we’ve survived right from day one thanks to the support of readers who value fiercely independent journalism that is beholden to no-one. To help us continue for another 35 future years with the same proud values, please consider taking out a subscription.

And for this weekend only, you can become a subscriber by paying just R2 a month for your first three months.